How the Railroad Built Duvall

Although mostly gone today, railroads completely changed the face of the Snoqualmie Valley during the early 1900s. They quickly became the primary transportation network in the region, not only connecting the cities, but in a number of cases actually helping create them. So why were the railways built, and where did they go?

In the early 1900s, the little town of Cherry Valley (near present day Duvall) underwent a dramatic transformation, driven by the introduction of the railroad.

Situated on the banks of the Snoqualmie River near today’s Taylor’s Landing Park, the community of Cherry Valley was centered around a market, grange hall, church, and a school (which had been constructed from the wood of a single old growth log). It was mostly isolated from the larger Seattle-Tacoma region, relying on boats as the main mode of transportation for timber, farm goods, and people.

But over time, the Snoqualmie Valley’s immense timber potential and rich agricultural soils attracted notice. In 1904, several railroad companies began vying to create a network of electric railways to connect it with the broader region. Yes, you read that correctly: electric railways. King County hydroelectric plants like the one at Snoqualmie Falls and on the Cedar River meant there was an easy, nearby power source for the train cars. In fact some companies, like Stone & Webster, took it a step farther and purchased the Snoqualmie Falls hydroelectric plant, giving them control of both the utilities and the street cars.

The planned network included a line from Everett to Seattle, Everett to Snohomish, Snohomish to Carnation (via Monroe and Cherry Valley), and Renton to Carnation (via Issaquah and Fall City). Over-competition led to the delay or abandonment of many of these plans, but a few succeeded, including an electric railway from Everett to Tacoma. This line, referred to as the Seattle-Tacoma Interurban, ran until December 30, 1928.

The route to the east, connecting Snohomish to Carnation (via Cherry Valley) ran across some challenges. The company that had acquired the right of way, Everett & Cherry Valley Traction, did not want to share their space with the Milwaukee Company which also had plans to build. In 1910, after several years of legal battles, a King County judge sided with the Milwaukee Company forcing Everett & Cherry Valley Traction to share their space.

After their loss, Everett & Cherry Valley Traction sold their right-of-way to the Great Northern Railway Company. Great Northern continued building the rail lines where Everett & Cherry Valley left off, but quickly discovered another issue. The town of Cherry Valley sat squarely in the way of the railway. So, in 1909, to appease the residents of Cherry Valley, Great Northern agreed to pay to move the buildings up the hill to the new town site (which would be named Duvall).

Some of these buildings are still standing today, including Duvall Flower and Gifts (formerly the Hix Market) and the Grange Café (formerly the Grange Hall). It took about six weeks to move the town up hill. In the years to follow dozens of other buildings were constructed alongside the original ones and today make up Duvall’s main street.

In addition to the buildings, Great Northern also had to move 20 graves. The company had to excavate a hillside and a portion of the Cherry Valley cemetery to install its rail line. The cemetery had mostly been abandoned due to flooding issues (which often caused for disruptive burials, when grave diggers would have to bail out water as caskets were being lowered), but there were still some that remained in the way. You can read more about the Cherry Valley cemetery in the Duvall Historical Society’s Newsletter.

Only six months after Great Northern finished installation, a rival railroad company, Milwaukee, arrived and squeezed another set of tracks between the Great Northern rail lines and the river. Both companies started to use their rail lines right away to haul timber and other freight, but it would take a while longer for passenger service to come.

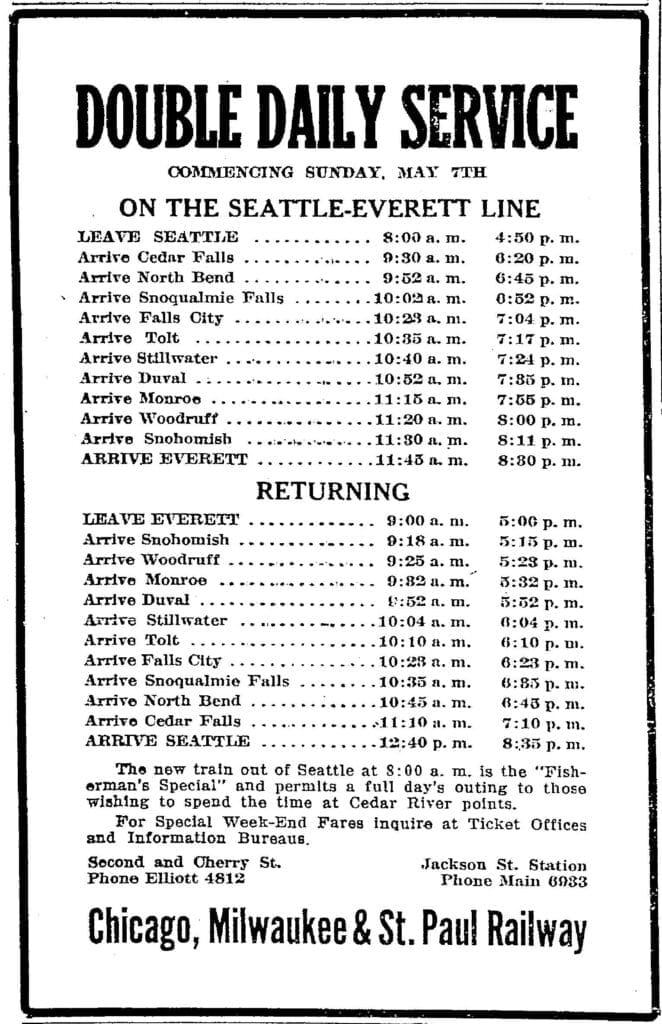

On May 7, 1916, the Milwaukee Company launched full passenger for the Valley. The line included stops from Everett to Cedar Falls (next to the current Rattlesnake Lake) then on to Seattle. You can see the first time table, published in the Seattle Times, below.

In the Golden Age of the railroads, trains were the lifeline for many towns. In addition to transporting goods they served as a primary way for how people to get around. While offering services for the residents in the Snoqualmie Valley, the railroad also helped fill out the towns. Ads for parcels in Cherry Valley and Tolt (now Carnation) could be seen in the Seattle Times. In fact, one ad that advertised parcels in Tolt for $25, was featured on the same page of an ad for suits for the same price.

In 1917, just a year after the full passenger service in the Valley began, the U. S. government required Great Northern to sell the Cherry Valley branch line to Milwaukee Company, reducing the competition along the route. In 1926 the Milwaukee Company pulled up its tracks, due to flooding, but continued service, leasing out the Great Northern’s track instead. Milwaukee continued service into the 1960s. On May 22, 1961, the last eastbound Milwaukee Road train left Seattle’s Union Station to Chicago, ending 50 years of passenger service to Seattle and the West Coast.

So, why was all this infrastructure built up, then just abandoned? In short: automobiles. The “Golden Age” of U.S. railroads lasted from the 1880s until the 1920s. The first production Model T Ford was produced on October 1, 1908, and by 1927, Ford would build some 15 million Model T cars. Government regulations also played a role. The regulations did not allow railways to set their own freight rates, abandon unprofitable routes, or rid themselves of money-losing passenger trains. Many railway companies were on the brink of collapse by the 1970s; and railroads like Penn Central, Rock Island, Milwaukee Railway, Reading, Jersey Central, and others disappeared.

Exploring in the Railroad Route Today

You can still ride on a portion of the Valley’s historic railroad today! The Northwest Railway Museum operates 3.5 miles of the historic Northern Pacific Railway between North Bend and Snoqualmie. Although you can no longer ride a train through the lower Valley, you can ride a bike through it.

Once the Milwaukee Company lines were abandoned, King County Parks acquired the section through the Snoqualmie Valley and converted it from rails to the Snoqualmie Valley Trail. The Snoqualmie Valley Trail is the single longest trail in King County’s Regional Trail System. It’s 31 miles long, running from Duvall to Rattlesnake Lake. The future vision includes a connection all the way to Monroe and Snohomish. On the south end it already connects to the Palouse to Cascades State Park Trail, another former railway line that continues all the way to eastern Washington and beyond.

The Snoqualmie Valley Trail is a great option for family biking in all seasons. Its relatively flat topography allows for easy navigation for all ages to enjoy – a beautiful trail meandering through forest and farm fields. You can find self-guided itineraries for day trips from Rattlesnake Lake to Snoqualmie and from Snoqualmie to Duvall.

In addition to experiencing the railway history by trail, you may eventually be able to get a taste of a historic electric rail car. The Northwest Railway Museum recently acquired a 1907 electric interurban train car, known as Car 523, which is the last known surviving Seattle-Tacoma electric interurban car. The Museum hopes to restore the car, and to someday have it run on its own power. You can read more about it here.

To learn more about Cherry Valley and Duvall history visit the Duvall Historical Society.