The First Black Union That Sparked the Civil Rights Movement

After the Civil War, the roots of the civil rights movement began to take shape within the Pullman Sleeping Car Company, the pioneer of luxury sleeping cars. In 1867, George Mortimer Pullman, the company’s founder, introduced ‘The President’—a luxurious sleeping coach equipped with an attached kitchen and dining car that offered personal service to passengers.

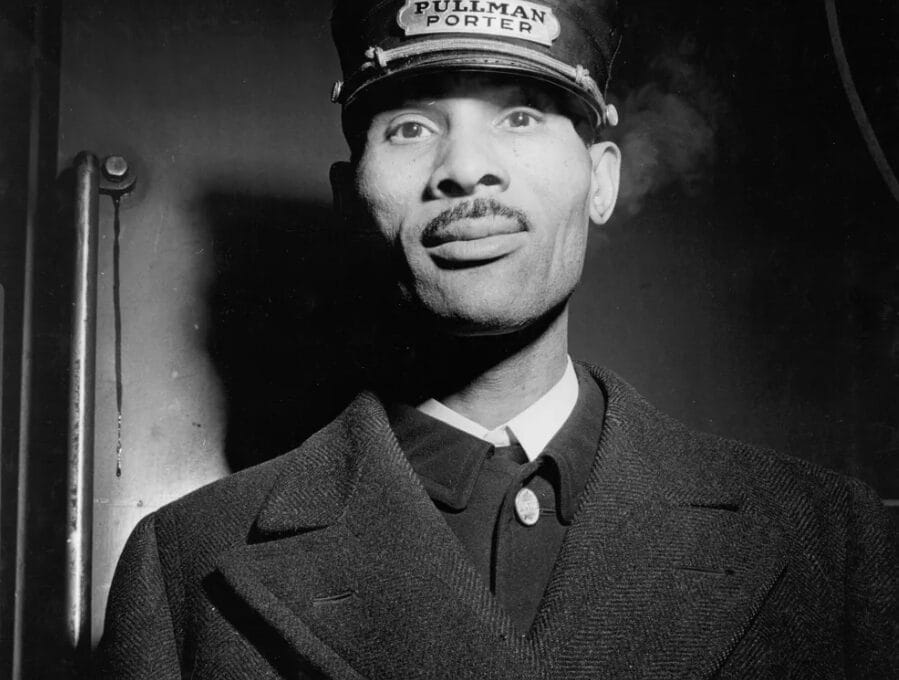

Pullman revolutionized train travel by employing a new labor force of porters who were willing to work for low wages—these were recently emancipated Black Americans. Employment by Pullman was considered prestigious as it offered steady work and the opportunity to travel across America in train cars that people of color were otherwise barred from using due to Jim Crow laws.

However, porters were not allowed breaks except for restroom use and were not permitted to sleep during their shift, unlike their white counterparts who had designated break areas and sleeping cars. Porters were expected to shine shoes, make beds, and carry luggage while remaining ‘invisible’ to white passengers. They served as valets, security guards, and bellhops, working long hours for wages that were far from a living wage.

Low wages forced porters to rely on tips from passengers. Tipping, originally a practice in Europe, gained popularity in the states to avoid paying formerly enslaved workers. The demanding nature of the job eventually led porters to demand more from their employers. With assistance from labor leader A. Philip Randolph, The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters became the first Black union to register with the American Federation of Labor in 1925.

Workers who openly supported union involvement were fired or moved to less desirable lines where work could be life-threatening. This made them hesitant to spread the news about union activities. Knowing they would face less scrutiny than men, the wives and female employees of the company collected union dues and hosted meetings. Led by Rosina Corrothers-Tucker, they helped keep porters and their families informed as the union continued to grow. Finally, on the twelfth anniversary of the union’s formation, Pullman granted porters lower hours and higher wages.

The union became a cornerstone in the foundation of modern civil rights, with porters continuing to play a crucial role in this fight. E.D. Nixon, a porter himself, played a pivotal role in organizing the 1950s bus boycott that made Rosa Parks a household name. Randolph, also heavily involved in the movement and a close friend of Martin Luther King Jr., organized the March on Washington where King delivered his iconic “I have a dream” speech. These men and women, often overlooked, worked tirelessly to sow the seeds that would grow into the fight for equal rights—leaving a legacy that persists to this day.