Roslyn’s Black Pioneers: Unearthing a History (Part 1/4)

Written by Alisa Weis, and originally published in the Northern Kittitas County Tribune.

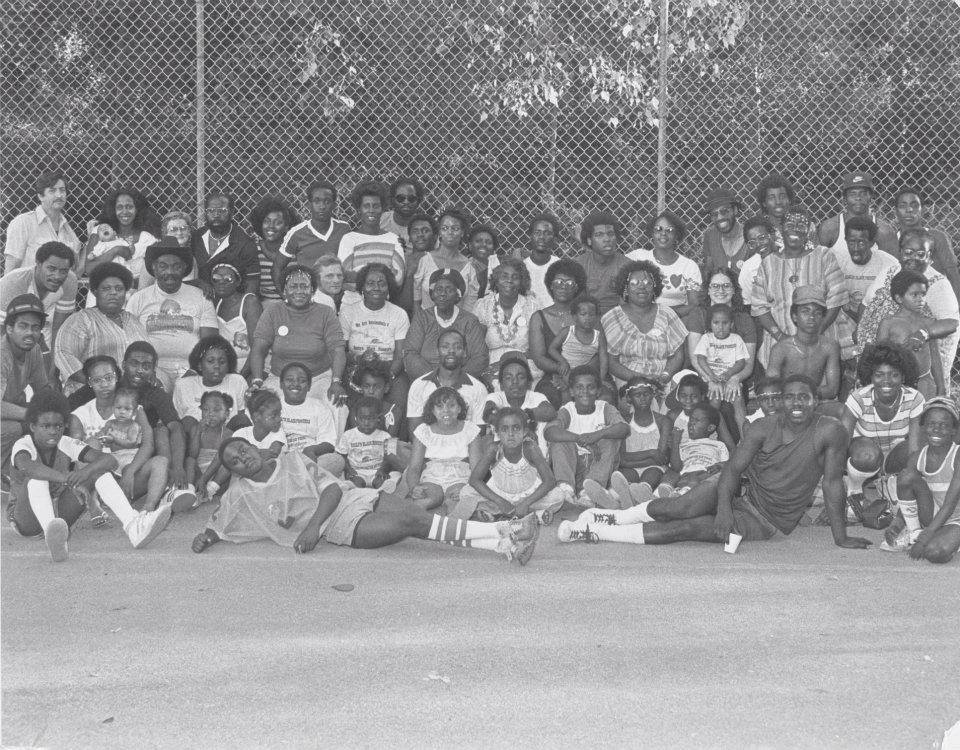

Every August the Craven family upholds an important tradition that began back in 1889. Passersby might take a glimpse of the large African American family and friends celebrating at the Cle Elum Park and not realize there’s more to the scene than a roasted pig, delicious homecooked sides, singing along with Marvin Gaye, and games for all generations. But walk a little closer, and visitors will start to hear bits of history preserved, especially from the living of Samuel and Ethel Craven’s 13 children, who are now in their eighties and nineties.

If you incline an ear, you’ll begin to note the substance of a little-known history. You’ll learn that the Roslyn Black Pioneer Picnic is a tradition that started as Emancipation Proclamation Day celebration. The Picnic was noted for its inviting atmosphere not only for family, but for the people of all backgrounds and colors. Newcomers and regular attendees were thrilled to feast on mutton stew and dance into the night on a constructed stage during the earlier years. Though the Picnic took a hiatus before WWII, it was revived in 1978 with the efforts of Beulah Craven-Hart, daughter to Samuel and Ethel.

For those unfamiliar with the origins of the small coal mining town, coal seams were discovered in Roslyn back in 1886. Under the ordinance of Logan Bullitt, the town was named Roslyn. It became a well-sought destination for more than 24 ethnicities as word spread that the land was coal rich. Some of the most noted populations included Serbians, Croatians, Poles, Italians, English, and Welsh.

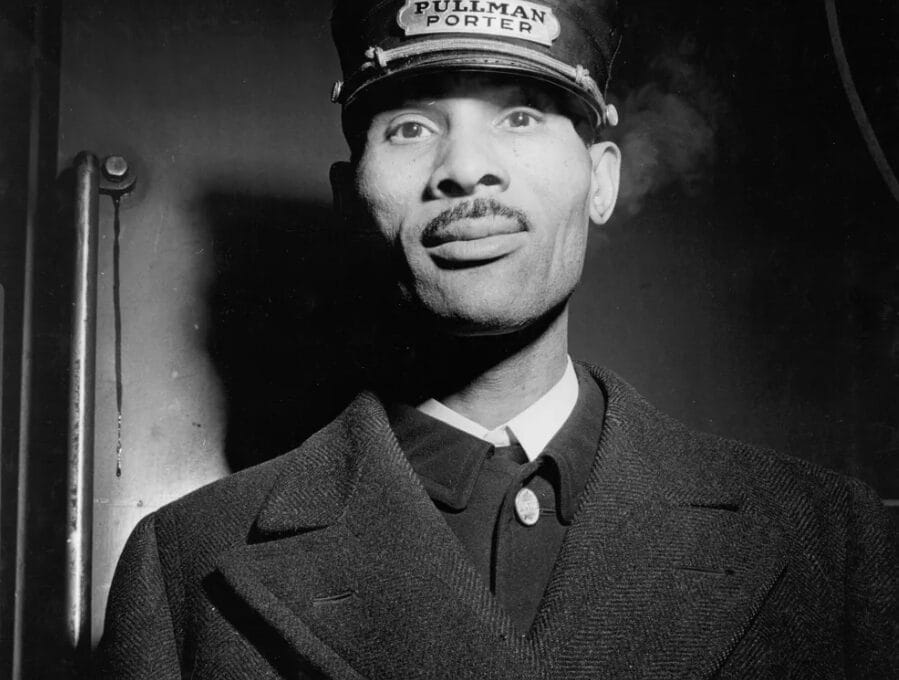

The Black miners’ presence started back in 1888/1889 soon after disgruntled miners united with the Knights of Labor and called for a strike. Dissatisfied with the long working hours, the poor pay, and the lack of safety conditions, the miners demanded a change and took to picketing. Not so fast, Northern Pacific Railroad said. Their answer was to bring in more than 300 African American miners from midwestern and eastern states to serve as a replacement over the next six months. It was greatest surge in African American migration to the state.

What follows is a nuanced history, one that is wrought with gains for those looking to the hope of a post Jim Crow America and setbacks because of some unwilling to honor the progress of an equal nation. “We can memorize what’s written in history (books),” said Harriet Joyce Craven, the matriarch of the family, “but we know that a lot is left out. History is often written by people who want control.”

Northern Pacific was strategic in their ploy, hiring Black businessman Jim Shepperson to do their bidding. Utter his name, and some of the Cravens will frown or tell you he was not to be trusted. With the use of brochures that boasted the benefits of working in the Pacific Northwest, “he was able to lure people with talk of good jobs and good pay,” said Ethel Craven-Sweet, the ninth and last of the Craven daughters and the one named after their mother.

Shepperson told Black miners of the promising employment they’d find in the west. He mentioned a new mine, the #3, where laborers were needed. Meanwhile, he failed to mention that a strike had broken out in Roslyn, vital information which would have changed the life course of many had they known. “The labor recruiters weren’t honest,” said Kanashibushan Craven, the eighth of the Craven’s daughters. “They talked about good jobs and wages, but it was a lie. Some smart Black men allowed themselves to be used.”

And despite the fact that Shepperson was responsible for the founding of the Black Free Mason Lodge: Knights of Tabor, two churches, and Big Jim’s Colored Club, his initial deception left a sour taste in the mouths of many for years to come. The first 50 or so Black miners to board the trains were from Streator, Illinois. Eventually, more than 300 workers would come from states such as Alabama, Kentucky, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Virginia in 1888 and 1889.

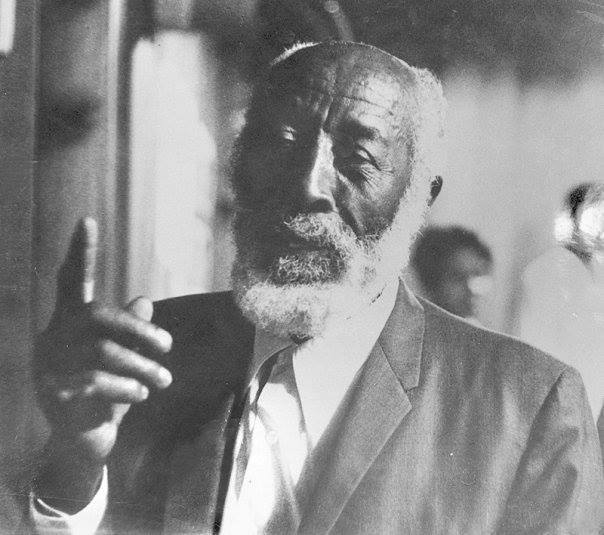

The Cravens’ link to the region is their grandmother, Harriet Jackson (Taylor) Williams, who at seventeen years old, arrived on a train with her young son, Fred. She was escaping an abusive first marriage and eager to make a new life for herself west of the mountains. She succeeded by homesteading over 250 acres. Today she is lauded for her bravery and fortitude. Her image graces the CWU project insert, “Through Open Eyes: Roslyn’s Black History” and appears on the tops of cakes at family get-togethers.

In 1902, the Cravens’ grandfather, David Williams moved to Roslyn from North Carolina and soon after he married Harriet. Four years later, in 1906, their mother, Ethel Florence Williams, was born. The first Black miners weren’t made aware there was a strike breaking out over their intended destination until Pinkerton guards joined them on board their trains in Montana. These guards were clutching rifles and handing out some to the passengers, alerting them to the trouble brewing ahead.

“We’re not strikebreakers,” Ethel Craven-Sweet, one of Samuel and Ethel Craven’s daughters, clarified, stressing that this derogatory term was placed upon them and has no part of their identity. “We’re Roslyn’s Black Pioneers,” she said.

Headlines from various publications in the Pacific Northwest tell of the turmoil that awaited the first African American residents. The Daily Oregonian August 20, 1888’s headline reads: “Probably Going to Roslyn: A Special Train Loaded with Negro Miners, Detectives, Winchesters.” The article goes on to tell how the detectives built a barricade of logs and wire to protect the Black miners upon arrival, knowing violence could ensue. Governor Semple sent telegrams to WA Attorney General Metcalfe, deeming the influx of Black workers an “outrage” and calling for the arrest of the armed guards (Historylink.org). But upon journeying to Roslyn himself, Semple was able to see that the climate wasn’t as tumultuous as he’d thought.

Were the out-of-work miners originally more rattled about their replacement’s skin color, their threatened job security, or both? It’s a question that presents itself even 120 years later. A close examination of written history tells us that the answer is complex at best. After all, a reported 200 white families left Roslyn in early 1889 after their hoped-for terms in the mines weren’t met. Many others returned to the mines and worked with their Black counterparts, reportedly looking beyond race to get a difficult job done. Historical sources remind us, it was difficult to discern one’s color underground. Working in such close corridors broke racial barriers and created unity unlike many other professions in the country.

A Contentious Reception

While it didn’t take long for Black and white miners to work together, what we know of the initial upheaval tells us that even progressive states like Washington left much to be desired on the road to freedom and equality. Though there are some telling headlines from the time, much of the wrong done is remembered not in writing, but in the memories of Roslyn’s residents.

A Seattle Press journalist wrote, “they came across as slaves, and as slaves they will remain in Roslyn” and then “at the muzzle of Winchester rifles, our free white laborers are displaced by slaves.” And also: “think of the injustice being done to free white miners at Roslyn.” A headline from December 30, 1888 from The Seattle Press claims that “mob reign rules in Roslyn tonight.” And then a month later, on January 28, 1889, the Tacoma Daily News reported: “Affairs at Roslyn: A Black Miner Shot at a Dance.” The Black miner was reportedly singing at a club. After refusing to stop at the insistence of a drunken white miner, the man was shot and killed.”

The response from the community is not widely recorded, if at all, but reports of subsequent Black miners still being brought to the region follow this early crime. In an article from The Tacoma Daily Ledger on February 15, 1889, it says that “about 300 Blacks arrive at 7 p.m. in eight coaches and three baggage cars.”

At one time, tempers over the incoming Black workers struck such a fever pitch that angry Knights of Labor miners dragged Mine Superintendent Alexander Ronald out to the train tracks and tied him down. A railroad brakeman leapt from the train and untied him at the last minute, saving his life. (Roslyn: Images through Time).

While widely reported that the Pinkerton guards did their due diligence in guarding the Black miners, the newcomers lived in fear and were made to live in crude shanties or tents in Jonesville, beyond the town of Roslyn where they’d thought they’d make their homes. “My grandmother carried a gun in her purse for protection,” Harriet Joyce said, echoing historical accounts that speak to the need for Black people to defend themselves against violence.

“Coal Towns of the Cascades” tell us the white miners who remained were more accepting of the company’s conditions and the fact that they’d work alongside Black miners once the strike ended. While there aren’t written accounts of further bloodshed, we’re told that, “discrimination took such forms as excluding Blacks from the city cemetery.”

Despite the absence of written records on burial rights for African Americans in those initial days, local historian/ Kittitas County Coroner Nick Henderson said that it was common knowledge that there are unmarked graves in Ronald, WA. In fact, he met with Dr. Raymond Hall, a CWU professor with an emphasis in Africana/ Black Studies, who wanted to use ground penetrating radar to identify the graves and place a memorial near the No. 3 mine in Ronald. Hall completed substantial research for the Africana and Black Studies program at CWU and was African American himself. He passed away in the spring of 2019, which left some of his Roslyn research unfinished. (https://www.cwu.edu/anthropology/raymond-hall).

Though there’s insufficient funding at this time, Henderson hopes that more people will become interested in honoring the first Black miners who died with a Memorial. “The area had been leveled by the NWI Company many years ago so we could not use GPR as they did many years ago,” said Henderson. When asked what she knew of unmarked graves, Harriet Joyce had further insight on the cause of the deaths of the first Black miners to the state. “There was a creek in Ronald where Blacks were murdered (when they first arrived here),” she said, confirming the century’s old rumor that there was in fact further violence over the new miners’ arrival. The place they were buried was called N– Hill. According to Henderson, that location is even listed on residents’ birth certificates, but there is strangely no mention of it in any recorded sources.

Within several years of their arrival, there was an established burial ground for Black miners. Anyone who visits the Roslyn Cemetery is undoubtedly fascinated by it: expanding over the hills, the graveyard is segregated, representing the 24 nationalities of people who came to Roslyn. Mt. Olivet, the Black Cemetery, eventually came into being by three Black women: Lilla Nichols, Eva Strong, and Sally Claxon (who was married to Jim Shepperson at one time), Harriet Joyce said.

Honoring their ancestors has, in part, encouraged brothers Will, Wes, and Nathaniel Craven to work as gravediggers at the Roslyn Cemetery over the years. It’s a work that their father, Samuel– a man noted for his strength—began, and they took on, though Wes is the only one who continues it today. The Cravens’ devotion at Mt. Olivet pays beautiful tribute to the Black pioneers who have passed, including some of the earliest Black miners who weren’t given markers. Though the Craven family is faithful in their maintaining the grounds of remembered loved ones, visitors also can’t help but reflect on the past and the Black pioneers who gave their all to make Roslyn such a thriving coal town.