Roslyn’s Black Pioneers: Pioneering Spirit (Part 2/4)

Written by Alisa Weis, and originally published in the Northern Kittitas County Tribune.

Read part 1 of this series here.

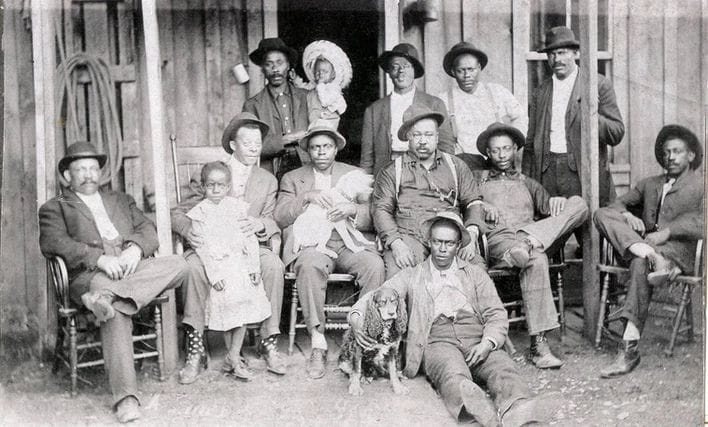

Back in 1900, 22% of Roslyn was comprised of African American residents. The majority of Black families arrived in 1888/1889, after the call for labor in the mines was sounded by Jim Shepperson, a Black businessman who failed to tell hopeful miners that a strike was ensuing in Roslyn until their trains were already in motion. Though the initial months in the Upper County were contentious between Black and white miners and not without violence, over time the feuds abated. Miners of different races and ethnicities worked together to complete grueling work underground. Many European miners, who weren’t pleased with their unmet working conditions or what they perceived as their “replacement” workers, left town in early 1889.

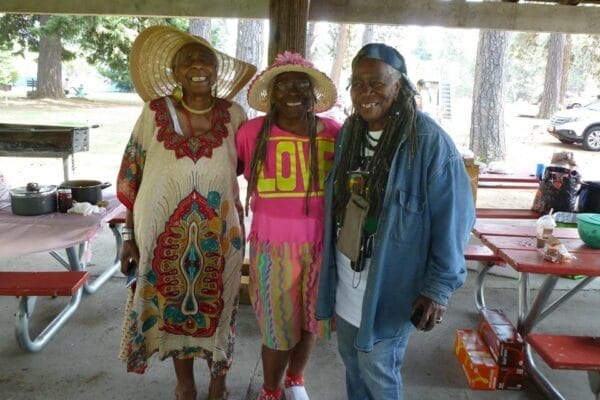

Over time some Black families left mining for other job opportunities across the state, many of them less harrowing than coal mining. Today there is only one remaining family from the original Black miners, the Cravens. But though they are one family, they have a history wrought with triumphs, sorrows, and perseverance that speaks to only those with a pioneering spirit. Their history is upheld by the descendants who speak of the strength of their ancestors and return year by year to attend events like the annual Roslyn Black Pioneer Picnic and New Year’s Celebrations.

At these uplifting gatherings, the family talks with pride of their resilient heritage. They are committed in passing this knowledge on to the younger generations. Who could forget that their grandmother Harriet had the tenacity and courage to travel alone with a young child and take to homesteading on her own? And who wouldn’t look to Mrs. Ethel Florence Craven for her calm and perseverance in raising so many children and still caring for others? And who could forget a man with as much strength, capability, and kindness as Samuel Craven?

Raised in Roslyn

Listen to the Cravens for a little while, and it won’t take you long to learn more of Roslyn’s storied history. While the town of Roslyn was comprised of over 24 different nationalities in the early 1900’s, there wasn’t a lot of intermingling amongst the races outside of working hours in the early days. The fraternal organizations throughout town had a self-segregating component to them. Among the Black fraternal organizations in Roslyn were the first Prince Hall Masonic Lodge in Washington territory and a lodge of the Knights of Pythias. Black women joined organizations like Eastern Star and Daughters of the Tabernacle. Black families attended Baptist and African Methodist Episcopal (AME) churches. (www.blackpast.org) While the fraternal organizations and churches were established to assist with members’ care, there were times members of differing organizations crossed paths to help one another. One such occasion came “when the entire community needed a school house, and the Black citizens of Roslyn offered up their church” (www.blackpast.org).

Despite such kindness and the friendships that formed because of it, some Roslyn residents held on to their prejudices. “Even when men were no longer fighting over the mines, prejudice fought for them,” said Kanashibushan Craven of racial climate that persists in the nation at large. “It’s so subtle that it cuts underneath.”

Even years beyond the initial strike, Kanashibushan said “it took a long time for race relations to improve in Roslyn. We were not welcome here.”

Though true that after the strike ended, many Blacks acquired “a social status unlike any they’d ever had before,” it’s suggested that the utmost reason was because of the railroad’s need for more workers (Coal Town of the Cascades). While some friendships formed between the races, the Cravens tell of personal blights they dealt with during their own growing up years, which came long after the first Black miners set foot east of the Cascade Mountains.

The Cravens’ father, Samuel, came to mine in Roslyn in 1922 from Texas. He’s still highly regarded for the impact he made, breaking barriers to assist his fellow miners and demonstrating a selfless spirit to those around him. “I got along with everyone (in Roslyn) because of my dad,” said son Will Craven. “He was athletic, and he saved a lot of people in accidents. He really understood mining.”

His sister Kanashibushan discussed her father’s attributes at length. “(Daddy) was tall, handsome, and gentle… I knew he was a helpful man because he’d always help anybody,” said Kanashibushan in an interview on her family lineage (2007). “He had a good sense of humor and a beautiful smile. A man came to the house (after my dad died) and he told me my dad he saved many people in the mines. And he was crying, this man was actually crying. And he must have been in his late 60’s or 70’s. He said what happened was the mine started to cave in, so the head person said, ‘everyone run.’ And then they ran and got out and then they looked around to see where this gentleman was. And my dad looked around and said he was back there. They said ‘somebody needs to go get him, and nobody would go back. But my dad went back. And they said he lifted a 1,000 rock and carried the man out like a baby…That’s the kind of man my daddy was,” Kanashibushan said.

Will said that their mother was a woman who kept boundaries needed to protect her family. His sister Ethel echoed this sentiment by saying their mother was her “daughters’ protectors” and a staunch disciplinarian, who “watched over her brood, which is a good thing.” Mrs. Craven raised nine daughters and four sons, in that order (one daughter, Georgia Mae, passed away at only 18 months due to health complications). When she wasn’t with her own family, Mrs. Craven assisted others as a midwife, with cleaning homes, and watching other children. While her children received their education alongside white students, Mrs. Craven established rules that would keep her children safe.

Her children were allowed to play with white students outdoors, but she didn’t invite them past fence in the 1940’s, as a safeguard against judgments on how she ran her household. The Craven children didn’t frequent many restaurants or other establishments as they grew up, given the size of their family, but some of them found fun in sports (baseball was an American phenomenon) or in walking the hill to the Roslyn Cemetery behind their house, especially on holidays.

The Cravens worked hard for everything they had, including a sought-after house on 2nd St that became their family home in 1943. Before moving there, the Cravens lived with in their grandmother’s 12 room boarding house without an indoor bathroom and a No. 3 metal tub for everyone to bathe in. It was through Samuel and his children’s picking of hops for long hours outside of Yakima that gave them the funds to purchase this new home, which came with more space, four bedrooms, and a bathroom. The Craven home on 2nd St remained with the family for 60 years until a fire devastated the structure in 2009. Thankfully, no one was injured. While sad to see their family home of so many years go, the Cravens’ memories of growing up in Roslyn can’t be compromised. Roslyn remains “home” to those born east of the mountains in the small, promising coal town.