Redlining in Seattle

Seattle has a history of complex and overlapping policies that maintained intergenerational wealth and power among Whites and excluded many Indigenous, Black, people of color, and immigrants from homes, schools, upwardly mobile jobs, and other institutions. Greater Seattle has been home to Coast Salish people for thousands of years. When the first White settlers arrived at Alki Point in 1851, Indigenous people lived in at least 17 villages and nearly 100 longhouses along Elliott Bay, the Duwamish River, the Cedar River, Lake Washington, and additional locations. As settlers arrived seeking land and resources, a “boom” period followed, and Indigenous people came to be seen as an obstacle to development. In 1865, Seattle’s first city council banned the Duwamish from living in the city. Between 1855 and 1904, nearly 100 longhouses were burned down in present-day Belltown, Pioneer Square, and West Seattle. Seattle’s displacement of Coast Salish peoples set the stage for a legacy of discrimination to follow.

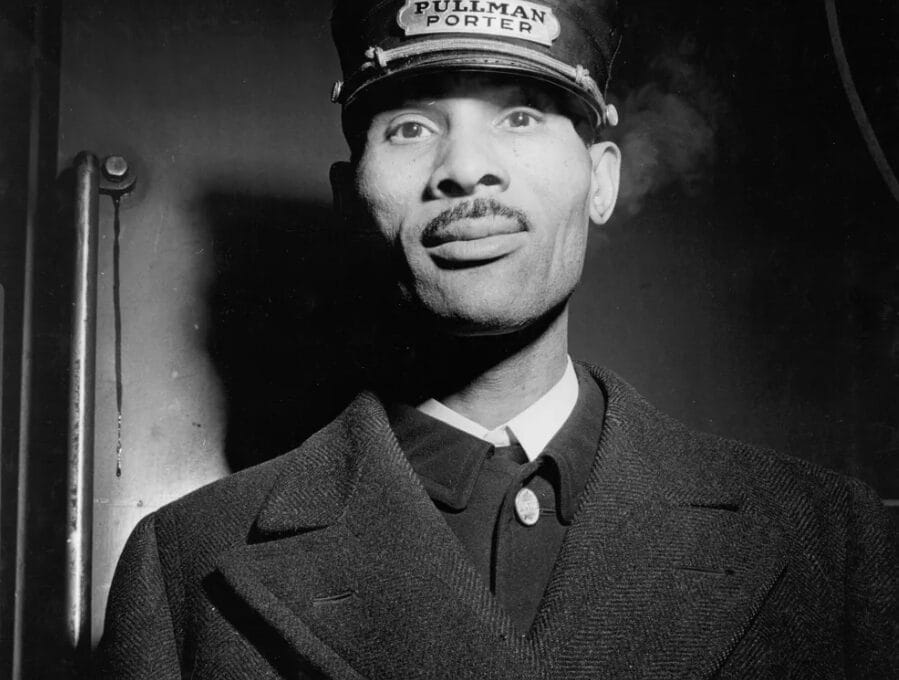

Until 1968, it was legal to restrict where people could live according to race. Racist housing covenants and deed restrictions inserted by homeowner groups and real estate agents were common in the 1920s through 1940s and applied to over 20,000 properties in Seattle and the Eastside suburbs–specifying “whites and Caucasians only” or prohibiting “Negroes, Ethiopians, Asiatics, Hindus, Malays” (Filipinos), and sometimes “Jews and Hebrews” from buying or renting in certain areas. Banks often denied home loans or charged higher interest rates to people of color, particularly African Americans. This is known as “redlining” or red areas drawn on a map labeling parts of the city as “hazardous” to lenders.

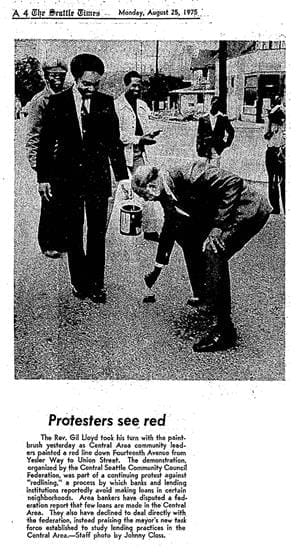

These practices restricted residents of color to certain areas, such as the Central District, Chinatown-International District, Beacon Hill, and South Park. In the 1960s and 1970s, an estimated 78% to 90% of Seattle’s Black population lived in the Central District. However, redlined communities responded with resilience. They created their own close-knit social networks, building vibrant multiracial neighborhoods. They also fought for civil rights, including the Open Housing Campaign of 1959-1968.

Following its passage, formerly redlined areas faced a new challenge: gentrification. Seattle has been experiencing another “boom period,” and as housing prices and land values increase, communities of color are pushed out of the very neighborhoods they were redlined into. In 2022, the Black population in the Central District zip code was less than 10%.

While redlining and gentrification isn’t unique to Seattle, the ways in which working class communities of color have collaborated to fight back are. Seattle has a distinctive history of multiracial, cross-community organizing for housing, services, and social justice. Grassroots activism continues to be key for the physical, cultural, and social preservation of Seattle communities.