How History Lost and Saved Snoqualmie Valley’s Elk

Visit the Snoqualmie River Valley at dawn or dusk and there’s a good chance you’ll get to witness a herd of hungry elk grazing on grasses, shrubs, and flowering plants. Emerging from the camouflage of tree cover in the spring and summer months, these ruminants fill their hungry four-chambered stomachs with large amounts of food when the bounty of native plants are most appealing. Herd sightings in open spaces like Meadowbrook Farm Preserve become more common at this time of year as the average male bull can weigh in at 875 pounds and needs to eat as much as 15 pounds of plants each day. Their hefty appetite often goes beyond the native plant varieties, wandering without invitation into the Valley’s enticing farms and gardens in search of delicious snacks.

Large herd numbers weren’t always the case in the Valley. When European Americans came to the Valley in the 1850’s, the native Roosevelt Elk (named after Theodore Roosevelt) quickly became overhunted because they were an easy source of protein for families to rely upon. In the absence of hunting laws or protected areas, the elk population dwindled until they were eventually ‘hunted out’ to either complete or nearly complete local extinction.

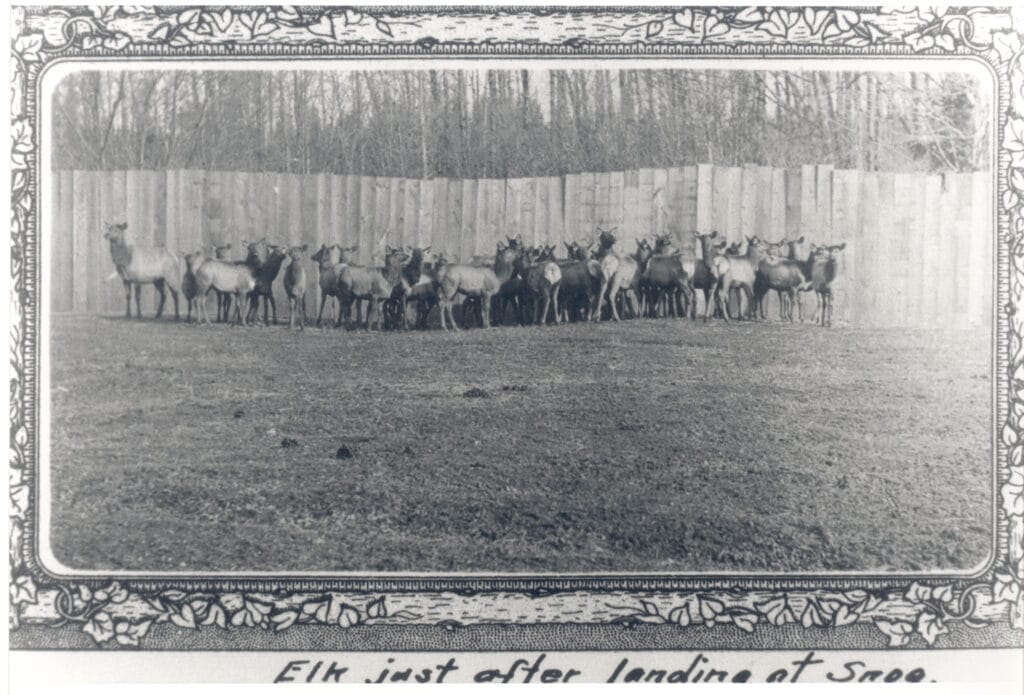

In 1913, the Seattle Elk’s club hatched a plan to bring a new herd of elk to the Upper Valley as a publicity stunt in commemoration of the club’s hosting of the national Elk’s convention. But it was easier to bring in a different subspecies rather than the original Roosevelt elk. So, they purchased a herd of Rocky Mountain elk from Yellowstone National Park in Montana, which was rounded up and shipped by boxcar to be released in the Upper Valley. The new elk herd arrived to the cheers of conventioneers and were immediately let loose into the Valley to adapt to their new habitat because it was simply too expensive to send them back. To the trained eye it was obvious that they were different from their native predecessors: The Rocky Mountain elk were slightly smaller, lighter in color, and with more slender antlers.

The original plan was to have the elk settled at Mill Pond island where they could graze on native vegetation without impacting local farms, but the plan didn’t work for very long. The island was a man-made creation, started as a natural oxbow in the river on property owned by the Snoqualmie Falls Lumber Company . And the vegetation proved to be no match for the hunger of 44 elk that were ready to double in numbers. A turning point came in 1932 when a severe flood inundated the island with water and forced the herd to the mainland.

Once out into the broader Valley, the elk became notorious for mischief, tearing down fences and feasting upon crops. Farmers grew irate by the damage and impatient with their own failed efforts to drive the herds out of the farmland. Frustrations boiled over as the number of elk rapidly grew when local hunters returned from WWII without much interest in taking up their rifles again to help control the elk population.

All of this came to a head in 1945 when the Valley experienced an extremely cold winter. The ground was covered with snow and ice, leaving little forage for the elk to survive on. Opinions were mixed on whether to intervene in their fate. Enough people that had a liking for the elk, brought food to them, but 20 of them still starved to death. The risk of the whole herd collapsing continued to rise and a new plan was hatched to save the elk from completely disappearing once again.

A joint rescue mission between the Washington State Department of Game and the Snoqualmie Falls Lumber Company ultimately was able to save 11 elk, including one “grand bull.” The mission involved four men working 10 days on the island to build a 150-foot rectangular corral to the edge of the island. Bales of hay were placed to bait the elk and encourage them to enter the trap. After a couple weeks, the trap was sprung and nine elk were caught, but the improvised rescue mission didn’t stop there. A reinforced truck had to be ferried across the pond and backed up to the corral where the elk were coaxed in for the ride back across the water. The other three remaining elk were later rescued. Together, the surviving herd was driven to a warmer location elsewhere in Washington to temporarily wait out the rest of the winter before returning.

Since that fateful winter rescue, the population has rebounded to about 500 elk now living throughout the Snoqualmie Valley. The challenges of living in cooperation with the elk, however, is one piece of history that has stayed the same. The reduction of natural predators like wolves and cougars, has encouraged more rapid population growth. This has meant that farmers are faced with the demands of constant fencing maintenance to protect their valuable investments. In 2009, the Upper Snoqualmie Valley Elk Management Group was formed to do proactive and collaborative efforts to minimize property damage or public safety risks associated with elk. The Snoqualmie Valley Elk Group also helps coordinate the tracking of herd numbers for scientific study, recreational, and educational purposes, as well as help provide information to the community on how to avoid and deal with elk damage.

Elk spotting: The central meadow, seen above, is popular with elk and great stop on the Meadowbrook Farm walking tour – plan your visit!

The next time you’re in the Snoqualmie Valley and want to see elk, keep in mind that the most likely time to spot them is in the early morning and late evening. During the summer months when the temperature is hotter, the elk will be more active at night. Keep an eye out for antler rubs on trees, tracks, and nipped shrubs for signs of activity. The best way to safely view elk is from afar and to never approach or get between a female and her calf. Another good time of year to observe elk is in the fall during their mating season in late September and October. The bugles of the bulls can be heard near dawn and dusk as they battle each other over females.

Know the signs of elk activity:

- Cloven hoof tracks

- Nipped shrubs and branches

- Droppings

- Hair on branches or fences

- Antler rubs on trees