Human RELATIONSHIPS WITH NATURE have shaped the landscape and the culture of the Greenway.

Since time immemorial, Indigenous people have tended to the lands now known as the Mountains to Sound Greenway, clearing areas for berries, planting for sustenance, carefully tending to forest health through judicious use of fire, and moving throughout their territories to harvest shellfish, salmon, elk, and other foods. When the Treaty of Point Elliott was signed in 1855, representatives from several local tribes and bands “exchanged” most of their traditional homelands to retain a number of rights, including to fish and forage at their usual and accustomed grounds and stations and to hunt and gather on open and unclaimed lands.

The rights of local tribes to sustain themselves and help care for their traditional lands is central to their identity, culture, and current way of life. Although these rights have not always been honored by subsequent governments, these “usual and accustomed grounds and stations” extend throughout the entire region of the Mountains to Sound Greenway and beyond, and the practice and celebration of these sovereign rights is an essential part of any recognition of regional or national heritage.

After the treaty making process ended in this area, the US Government acknowledged tribes’ sovereignty by executive order or the federal recognition process. These tribes have reservations and homelands for their people within or near the Greenway NHA. The lands of the heritage area are critical for their culture and way of life.

In the nineteenth century, white settlers asserted a different relationship to the mountains, forests, and waterways of the Greenway. Abundant fish, timber, and minerals were viewed as an economic opportunity, along with the potential to develop farmland and trading connections with the northern Pacific Rim. The resulting settlement transformed the region as forests were leveled, waterways dammed and diverted, and large areas of land were taken over by urban development.

After an initial wave of fur trappers who arrived in the early 1800s, the earliest settlers to the Greenway came in search of ranching and farming opportunities. West of the Cascades, the extensive and fertile prairies of the Snoqualmie Valley provided ideal grounds for farming, with hops being among the first crops to be cultivated widely for export. Many Asian immigrants who initially came to the United States to work on the railroads or in lumber camps turned to agriculture, and by the 1920s, Japanese farmers produced 75 percent of Seattle and King County’s vegetables and half of its milk supply. Small truck farms dotted flat areas throughout eastern King County, and in downtown Seattle, the Pike Place Market was founded in 1907 and quickly grew to be one of the nation’s largest and most famous farmers’ markets.

On the eastern side of the mountains, the lush prairies that made the area attractive to cattlemen were quickly turned into prime agriculture lands for settlers with the development of irrigation. By the 1880s farming had eclipsed cattle ranching as Kittitas County’s most lucrative enterprise, with hay, wheat and, later, alfalfa. The Bureau of Reclamation became involved in Kittitas irrigation in the 1920s, creating three reservoirs and an extensive canal network (the Kittitas Division of the Yakima Project) over the next decade.

Early settlers were quick to harness the power of water, as an agricultural resource, transportation mode, and energy source. They also used water to reshape the landscape, setting up steam-powered sluices to regrade the contoured landscape around downtown Seattle. Former state governor Eugene Semple led a truncated effort to build a canal from the Seattle waterfront to the south end of Lake Washington by moving fill from one spot to another which filled in the mouth of the Duwamish River and destroyed 1,400 acres of tidal flats and nearshore habitat.

Semple’s earthmoving schemes eventually lost out to business rivals on the north end of town who were intent on building a shipping route from Puget Sound to Lake Union. The construction of the Lake Washington Ship Canal, completed in 1916, lowered the level of Lake Washington by 9 feet and changed the hydrology of rivers 20 miles to the south. As a result of this landscape-changing engineering, the Black River ran dry, and Lake Washington, which used to drain out its south end into the Duwamish River, now flows north through the Ship Canal and into the Puget Sound. At the same time, the Cedar River was diverted from the Black River into Lake Washington.

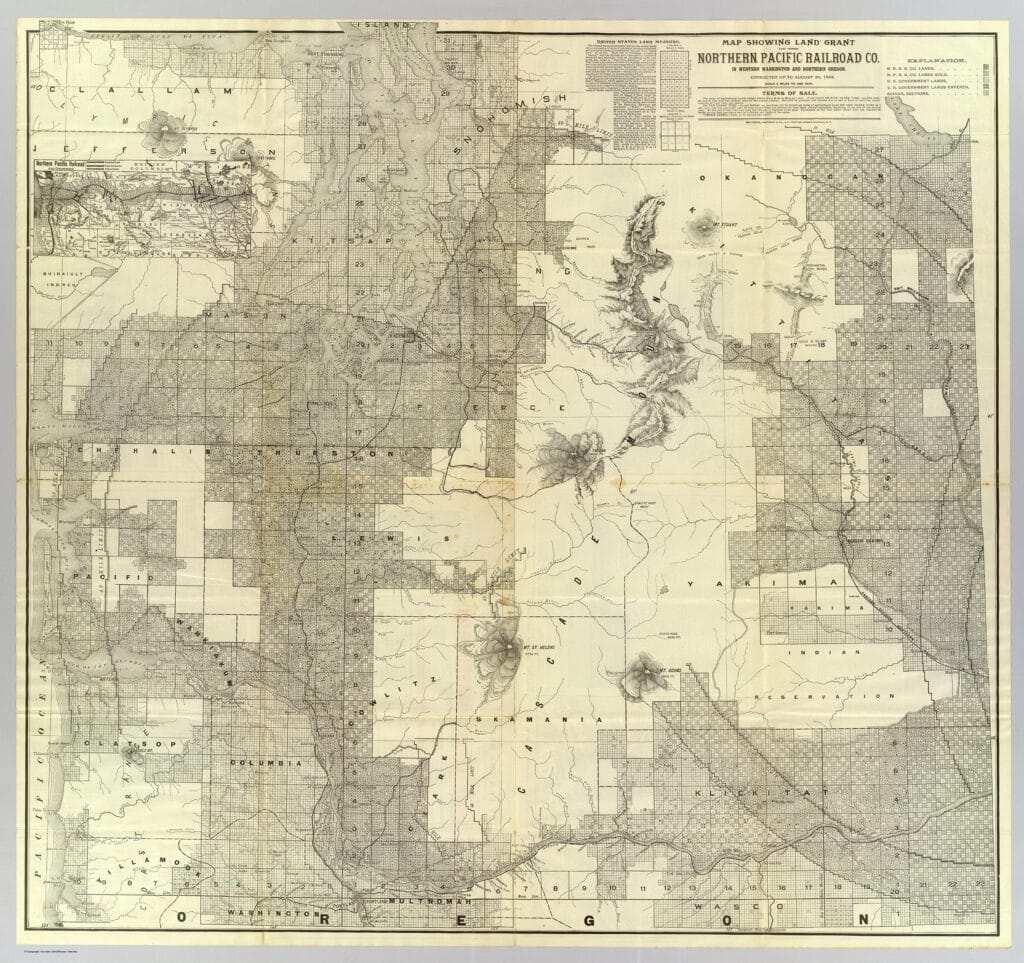

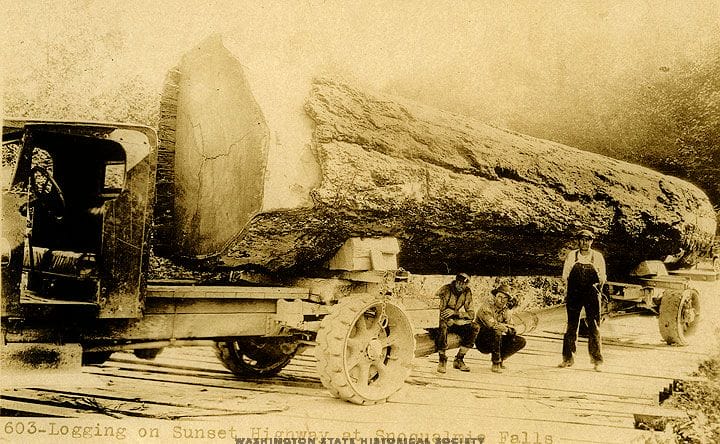

The timber industry as it developed in the Mountains to Sound Greenway also had an outsized impact on the physical features, ecological balance, and cultural practices of the region. Early settlers were quick to capitalize on the seemingly endless bounty of local forests. Henry Yesler’s sawmill opened on the Seattle waterfront in 1853, and Yesler quickly amassed a fortune and considerable political clout. But what truly tipped the scales on industrial logging practices was the Northern Pacific Railroad land grant, legislated by Congress and signed by President Lincoln in 1864. This privatization of massive quantities of federal land in the Cascades changed timber’s business model, transforming the industry from a collection of small, temporary operations along the coast to industrial-scale logging.

Federal grants to individuals made through the Homestead Act of 1862 were no larger than 160 acres—an area too small to sustain ongoing timber operations. In contrast, the Northern Pacific Railroad received every other square mile of land (640 acres/square mile), stretching 40 to 50 miles on either side of the railroad right-of-way in a checkerboard pattern. It was the largest land grant in American history: 40 million acres—an area larger than New England, constituting two percent of the land mass of the contiguous United States. This change in land ownership, combined with the advent of steam technology brought west by the railroad, quickly transformed logging into Washington’s largest industry.

Many working forests continue to operate in the Mountains to Sound Greenway, although forest management practices have evolved away from widespread clearcutting and streamside devastation. In other parts of the Greenway, forest managers have curtailed logging where ecological needs, carbon sequestration, or recreational interests have displaced industrial timber.

Mining also developed as an adjacent industry to the railroads. Coal seams in Cle Elum and Roslyn provided fuel for the steam-powered locomotives of the Northern Pacific, while coal mined in modern-day Newcastle and Bellevue was shipped south via Seattle to San Francisco. Numerous other small mineral claims developed in the mountains of the Greenway, some finding small measures of copper, nickel, and gold. Modern day prospectors continue to stake claims and seek gold in the streams around Liberty. But coal, and its railroad-driven market, remained king for half a century.

After nearly a century of resource extraction and exploitation, the region began to see a fundamental shift in its understanding of the Greenway’s natural assets as a finite resource. As part of a national movement to protect wild space and clean up the environment, conservation took root in the Greenway, with efforts to clean up Lake Washington and establish farmland preservation initiatives. By the mid 1970s, a great deal of work had been done to protect the crown jewels of the region—iconic natural areas preserved as federal Wilderness, State Parks, and state-protected Natural Resource Conservation Areas (NRCAs). That work continued as wilderness areas were expanded and the City of Seattle acquired complete ownership of and ended logging in the Cedar River watershed to protect its primary drinking water source. In other parts of the Greenway the protection of working farms and forests was recognized as providing valuable barriers to residential sprawl. At the same time, local residents began seeking out open space and trails in ever-greater numbers.

Outdoor recreation has long been an inherent part of the culture of the Mountains to Sound Greenway, with traditions linking directly to the development of railroads and timber access. Railroads first opened up the craggy mountain peaks of the Cascades to alpine recreationists in the late 1800s. Many early expeditions led by The Mountaineers (an outdoor recreation and conservation organization formed in 1906) were in the Greenway, in locations like Meany Lodge at the Stampede Pass station on the Northern Pacific, and at Snoqualmie Lodge near the Milwaukee Road station at Snoqualmie Pass. The Milwaukee Ski Bowl was one of the ski areas at Snoqualmie Pass that is now known as Summit East. While passengers no longer ride trains over Snoqualmie Pass, thousands of cyclists, hikers, and equestrians ride the rail-trails built on historic rights-of-way such as the Coal Mines Trail, Sammamish River Trail, East Lake Sammamish Trail, Cedar River Trail, Burke-Gilman Trail, and Palouse to Cascades State Park Trail (the longest rail-trail in the country and a significant part of the nascent Great American Rail-Trail).

Many locations throughout the Greenway NHA have become especially popular – often too popular – among hikers, climbers, mountain bikers, and other recreationists. Rock climbers frequent Little Si, the “Exit 38” routes, and climbing areas near Snoqualmie Pass where alpine climbing skills and techniques were pioneered. Kayakers and rafters float the forks of the Snoqualmie River and the Yakima, both waterways where techniques for safely navigating rivers were pioneered. Snowmobilers and cross-country and downhill skiers abound off Snoqualmie Pass and in Kittitas County, where Nordic ski jumpers were among the first pioneers of the winter sports heritage that has developed over the past century. The Mountaineers lead youth programs and rock-climbing trips and classes in the Alpine Lakes Wilderness Area, where they are joined by alpinists and climbers from around the state and beyond. The trailheads at Rattlesnake Ledges, Mount Si, and Snow Lake, are among the Greenway NHA’s most popular, and visitors will find fellow outdoor recreationists there almost any day. Mountain bikers enjoy the challenge of the Greenway NHA’s rocky, rooted trails in the Tiger Mountain, and Raging River State Forests.

The attraction to pursuing outdoor recreation in the Greenway NHA is not coincidental; it offers some of the best outdoor recreation opportunities within a one-hour drive of a major metropolitan area in the U.S., if not the world. Importantly, these recreational pursuits are more than activities that occur in the Greenway NHA; they are interwoven in the heritage of the region with innovation through equipment development, refining techniques to safely enjoy the outdoors through different sports, fostering a culture of stewardship, and advances in safety being fundamental to the development of outdoor recreation in this landscape that has spread far beyond the region. Indeed, several of the world’s leading outdoor gear companies were founded and remain based in the Greenway where easy access to the outdoors provides ample opportunities to test and refine gear.

Outdoor recreation in the Greenway NHA has contributed to a needed transition from extraction to protection through recreational use of the land and the fostering of a conservation ethic in its users. Recreation is not without its negative impacts though as increased visitation contributes to overcrowding at trailheads, overwhelmed sanitation facilities, disturbance of wildlife and sensitive habitats, and impacts on tribes’ cultural sites and treaty rights . Recreation requires good management and vigilant action to prevent overuse and damage to the ecosystems, tribal rights, and the experience of others within the NHA. Developing recreational and educational opportunities while keeping a balance compatible with healthy ecosystems is a key goal of the NHA.