The Greenway provides CORRIDORS for wildlife migration, fish passage, and human travel.

The Greenway NHA is a rugged landscape whose very name and concept evokes passage: Mountains to Sound. River valleys and lakes provide the easiest paths of travel for fish, animals, and humans. Salmon return home to spawning beds on all three major rivers of the Greenway NHA: the Yakima, Cedar, and Snoqualmie Rivers. As conservation efforts have begun to stitch habitat back together after a century of fragmentation and extraction, iconic species including wolves and wolverines have found their way back into parts of the Greenway. For human travelers, footpaths traced through the mountain passes were paralleled and overtaken by wagon roads, then railroads, highways, and then trails again.

The three watersheds of the Greenway NHA (the Upper Yakima, the Cedar-Lake Washington, and the Snoqualmie) saw large runs of anadromous fish before white settlement brought about habitat destruction, dam building, and overfishing. The Yakima River provided passage for spring chinook, summer chinook, coho, and sockeye salmon as well as bull trout and steelhead. The Cedar River hosted important runs of coho and chinook, while kokanee salmon were found throughout the Lake Washington watershed. Coho, chinook, pink, chum, and steelhead ran the length of the main stem of the Snoqualmie River up to Snoqualmie Falls. Above the Falls, native rainbow trout and cutthroat can be found in all three forks of the river. Today, the many anadromous runs of the Greenway are the focus of large-scale conservation efforts, with tribes providing important leadership and initiative to restore habitat and recover diminished populations.

Lakes and rivers were also pathways for human travel, with canoes providing transportation throughout the Puget Sound basin. The path of the South Fork Snoqualmie River leads to a low pass in the Cascades—Snoqualmie Pass—from which travelers can easily drop to the headwaters of the Yakima River at Lake Keechelus and from there continue to follow the Yakima to what is now Ellensburg. Elk and other wildlife follow similar corridors with the changing seasons as they migrate for forage.

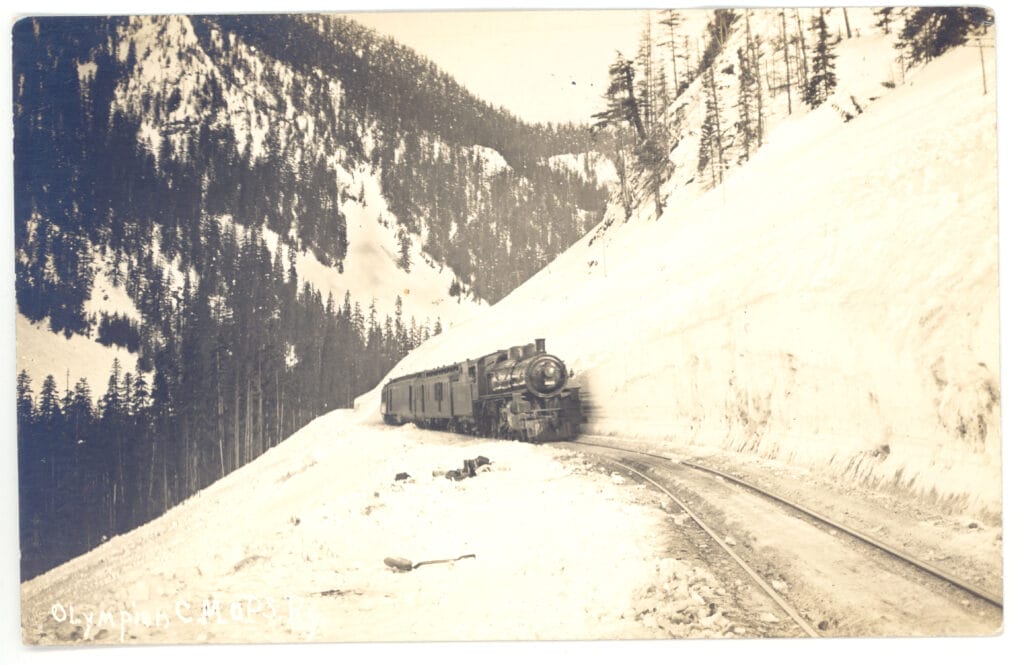

Wagon roads and then railroads later followed these same river paths and mountain passes, from the arterials of the transcontinental railroads to the smaller lines that ferried timber and minerals to market along tributaries of these riparian thoroughfares.

The construction of the Northern Pacific Railroad and the Milwaukee Road over the Cascade Mountains in the late 1880s/early 1900s transformed what some considered the last frontier of the continental United States. A key strategy in the promotion of the transcontinental railroads was the idea that a nation could be built through its infrastructure. The railways provided a route for commerce, transport, and settlement. In 1880, the population of Seattle was less than 4,000. Thirty years later, with the arrival of the railroads and the surge in immigration related to the Yukon Gold Rush, Seattle’s population had grown to more than 237,000 people. New residents came from the Midwest, the East Coast, and California, as well as from further afield and abroad: Canada, Germany, Sweden, England, Japan, and China.

The transcontinental railroads, and later the Sunset Highway and Interstate 90, connected the Atlantic seaboard and the Great Plains with Seattle and Puget Sound—and to the Pacific beyond. In 1896, Seattle became the first port in the mainland US to establish regular commercial service between the US and Japan, and soon became the nation’s hub of trade with Northeast Asia. The US exported lumber, coal, wheat, and metals, while silk, tea, and ginger came in via ship through Puget Sound and then continued eastward via rail. The Milwaukee Road, an electrified transcontinental train route through Snoqualmie Pass, ran specialized “silk cars” to quickly and safely carry this fragile cargo to New York. The Milwaukee Road’s early advertising emphasized the tourist attraction of traveling by train. Stations along the route through Snoqualmie Pass provided early access to winter recreation as skiing and winter sports were being developed at the Pass.

The advent of the automobile at the turn of the twentieth century brought highway development along the route of the old wagon road that crossed at Snoqualmie Pass. Highway engineers improved grades, built bridges, and blasted out cliffs to make for smoother passage. The Sunset Highway, opened in 1915, climbed up to Snoqualmie Pass from Renton before the construction of a floating bridge across Lake Washington provided a more direct route from Seattle to Ellensburg. The Highway provided an essential cross-state connection and helped bring early recreation travelers to the mountains. Today, more than 30,000 vehicles cross Snoqualmie Pass on I-90 every day, a figure that surges on weekends and holidays.

As these east-west connections were forged in steel and then in concrete, they were developed at the expense of wildlife migration corridors stretching from the North Cascades down to the southern reaches of Mount Rainier. With this vital link severed, the genetic diversity of the wildlife populations became limited and their ability to adapt to a changing climate was hindered. An important opportunity to mitigate the impacts of highway construction came with the ongoing I-90 Snoqualmie Pass East reconstruction project. The Greenway and other local conservation partners worked with the Washington State Department of Transportation to design and secure funding for a series of innovative wildlife bridges and underpasses to facilitate north-south migration. Combined with ongoing work to remove fish barriers related to highway construction, the region is taking important strides to rebalance transportation needs with considerations for wildlife.

Ongoing consolidation of surrounding forestlands further strengthens these north-south migration corridors. Congress initially granted a forty-mile corridor of checkerboarded lands to the railroads as a means of helping fund their construction and encourage homesteading and development. This legacy resulted in highly fragmented forest ownership patterns that proved onerous for government agencies and private landowners alike, no less for wildlife trying to move through highly variable habitat. Land swaps, private sales, and public land acquisition in the I-90 corridor around Snoqualmie Pass have begun to stitch back together swaths of contiguous habit connecting north and south, east and west across the Greenway NHA.

Many of the state’s most popular trails are among the more than 300 that branch out along I-90 between Seattle and Ellensburg in the Greenway NHA. From the four-season foothill trails on Cougar, Squak, and Tiger mountains to Rattlesnake Ledge, known as daʔšədabš to the Snoqualmie people, to the awe-inspiring mountain trails leading into Alpine Lakes Wilderness, a visitor to the Greenway NHA can travel by foot, horse, bike, and motorized recreation to visit the multitude of natural wonders in the Greenway NHA. Some of the Greenway NHA’s most popular trails are located at Mt. Si, in the Middle Fork Snoqualmie River Valley and at Snoqualmie Pass.

Travelers along the Pacific Crest National Scenic Trail trace a path along this north-south corridor, moving through consolidated checkerboard land around Snoqualmie Pass before stepping back into Congressionally designated Wilderness. East-west trail users in the Greenway NHA now navigate along the former railroad beds of the Northern Pacific, Milwaukee Road, and other branch lines. The Mountains to Sound Greenway Trail, stretching from Ellensburg to Seattle, and the Palouse to Cascades Trail, is merely an incarnation of centuries of human travel along this scenic corridor.