The Town that was Swept Away

On December 23rd, 1918 a pregnant Emma Koester slept snugly in her row house in Edgewick, just outside North Bend. What Emma didn’t know was that something was about to happen that would change her life forever. Emma was one of the only people to record the events of that fateful night—the letters that she wrote to her sister afterwards shed light on an event that would sweep a town away.

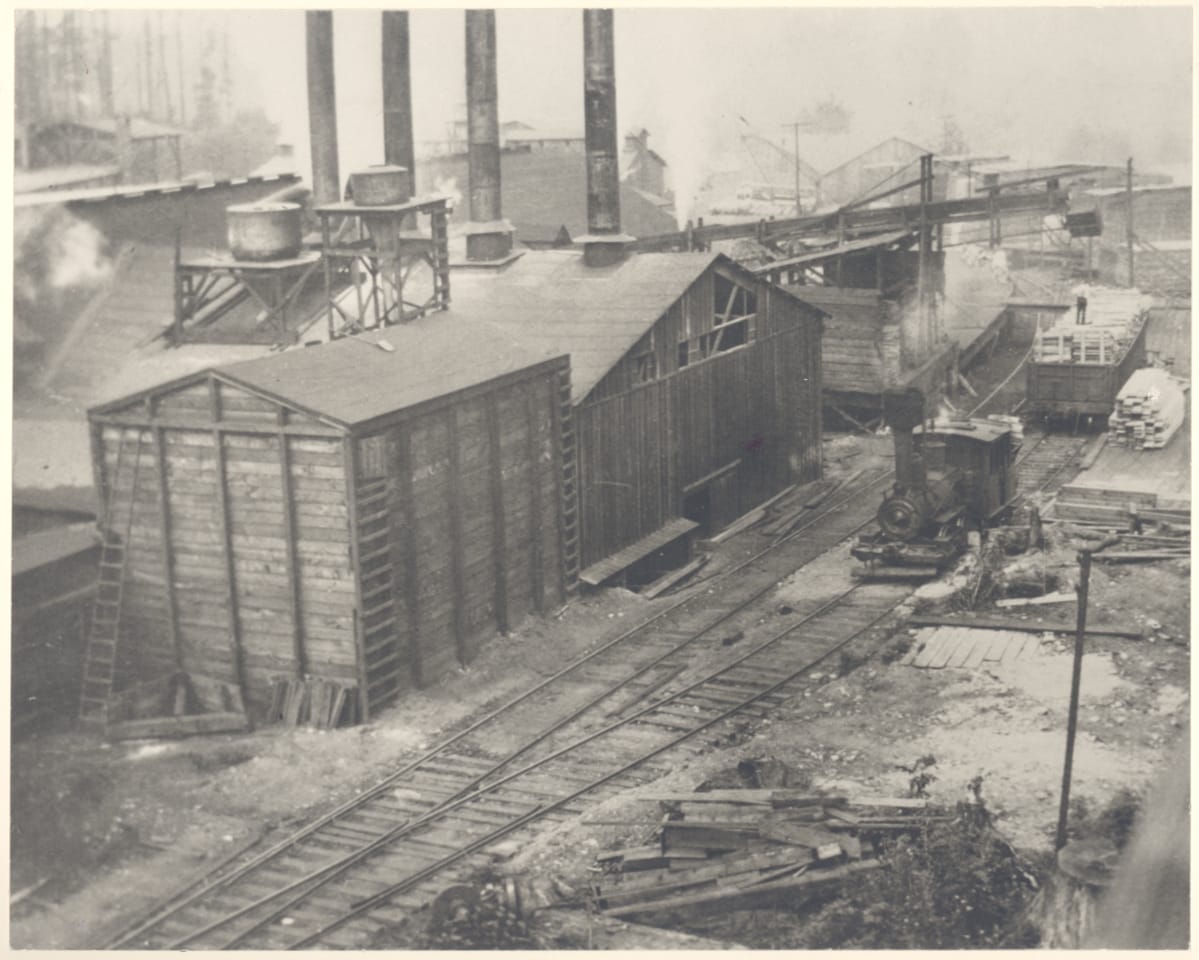

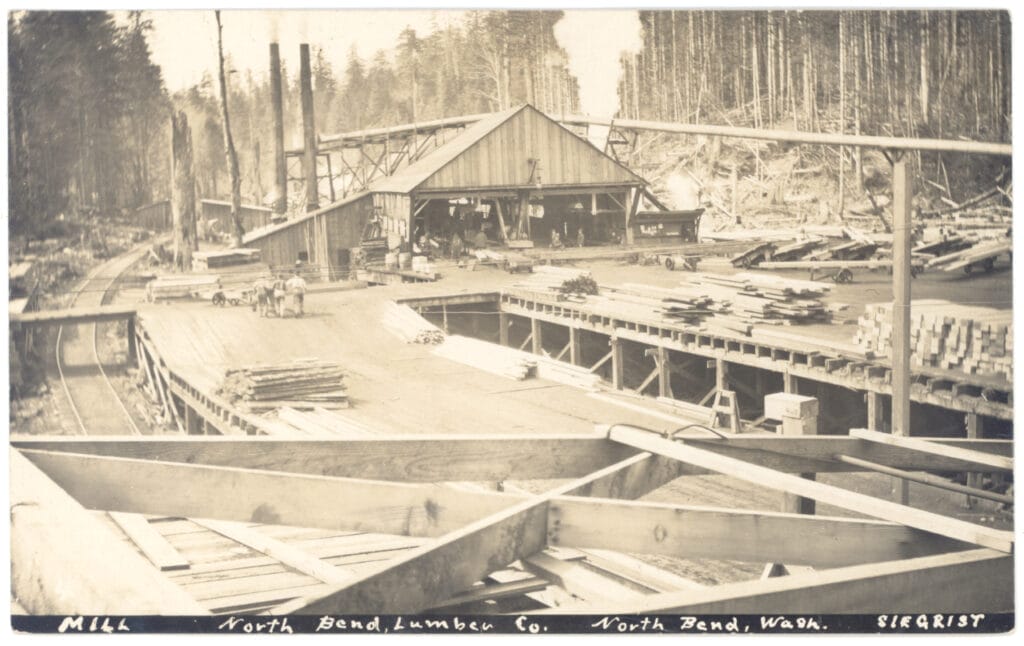

The North Bend Lumber company built Edgewick as a company town located on the South Fork of the Snoqualmie River. It built the first sawmill in Edgewick in 1906, and by 1918 the town consisted of three mills, 18 identical row houses for families, a bunkhouse for single workers, a kitchen, a dining room, and a company store. The mill played a really important part of the war effort. Sitka spruce, a species unique to the Northwest, was a vital material for constructing aircraft for World War I because of its exceptional strength and low weight.

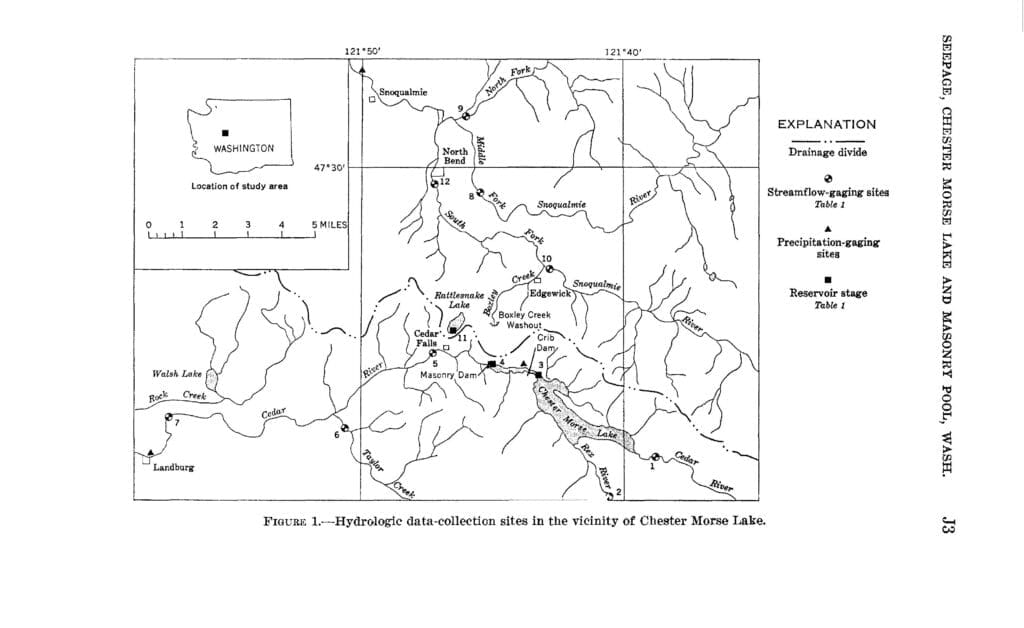

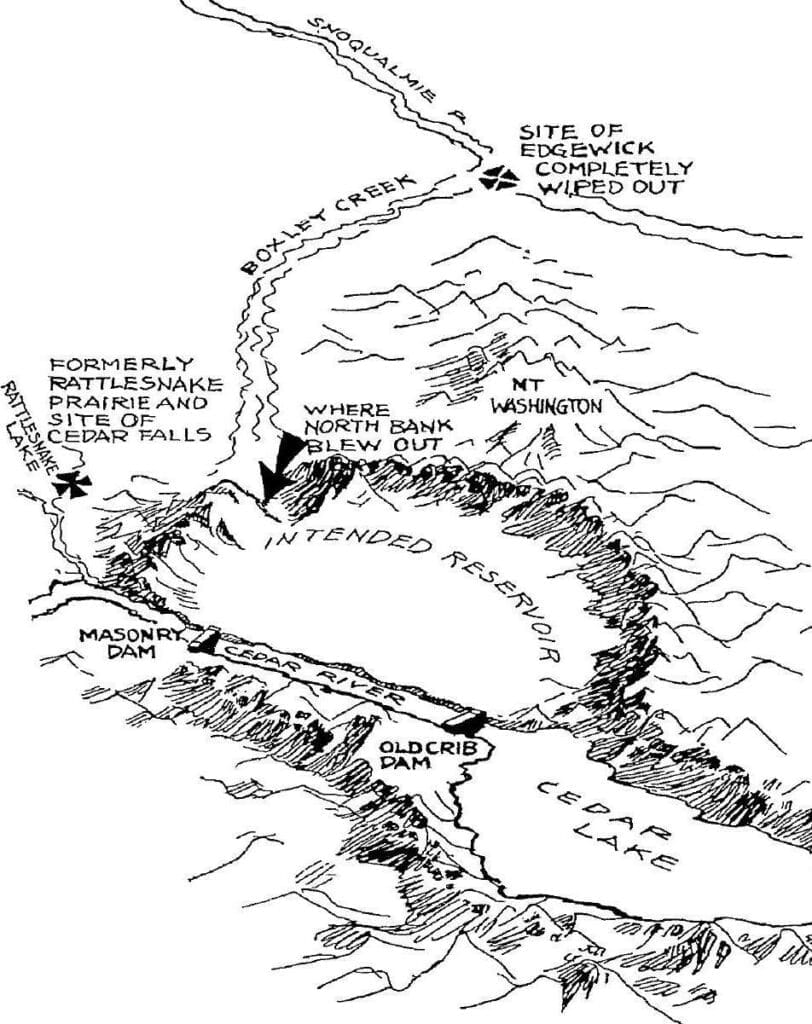

Running along the town was Boxley Creek, a tributary of the South Fork Snoqualmie River, fed by Rattlesnake Lake. The lake had been formed only three years earlier through underground seepage caused by the installation of a dam on the Cedar River. The City of Seattle had built the dam to harness electricity, but when the dam was built it caused a prairie, also the site of a town called Moncton, to fill and become a lake. (You can read the full story about Moncton on our blog post The Town that Slowly Sank.)

In October 1918, City of Seattle completed construction of the masonry dam (the very same one that has caused the problems for Moncton), and the reservoir began to fill up. As it filled, water continued to seep into Rattlesnake Lake and in turn increase the flow to Boxley Creek. That December was extremely rainy in the area, causing the water to rise even more and saturate the land around it.

What happened next would have dire consequences downstream. On December 23rd, the hillside above the dam had become over-saturated, and a landslide erupted. Half a million cubic yards of earth and gravel cascaded down the hillside and within minutes, the little Boxley Creek turned into a 150-foot wide river, heading straight for Edgewick, straight for Emma.

This would not be the first time hardship had come her way. Born and raised in eastern Washington, Emma’s mother died when she was 4. After her mother passed, she was sent to live with her Grandmother in Yakima. As her grandmother’s health declined just a few years later, Emma was placed into an orphanage.

Fortunately for Emma, a couple from Edgewick, named Charles and Christine Tiffin, decided to adopt her and brought Emma back live with them. In Edgewick she met her future husband-to-be, Private Ed Koester. Ed was a soldier with the Spruce Division, a unit of the Army established to produce high-quality Sitka spruce timber for World War I aircraft, and stationed in Edgewick to oversee spruce production for the Army.

Just months after Ed and Emma were married, Ed was sent to Fort Vancouver in Vancouver, Washington to muster out of the army. WWI had ended on November 11, 1918 and soldiers in the area were sent to Fort Vancouver so they could be discharged and sent home. Shortly thereafter, he contracted Spanish Influenza, which quickly progressed into pneumonia. On December 15, 1918 Ed passed away, leaving a newly pregnant Emma behind to live in their house in Edgewick.

Just a few short days later, the giant flood hit the town. At about 2:30 a.m., while Emma and the rest of the town slept, night watchman Charles Moore began to notice something wrong. Boxley Creek had begun widening by a foot every couple of minutes. He knew something must have given way upstream and jumped into action. He tied down the mill whistle to get the town’s attention then screamed for everyone to get up and out of their houses.

People rushed out of their homes and began to congregate in the center of town when they heard a horrible crunching sound followed by a thunderous roar – the dam reservoir had just given way. Families frantically rushed uphill as the water rose ankle deep, then waist deep, then up to their necks as they climbed their way up and out of the path of destruction.

Miraculously, everyone – including Emma – made it out of their homes and to higher ground. They spent the night up in the woods on the hillside listening to the sound of their town being destroyed. Huddled together over a fire on the hillside, they waited for the sun, and Christmas Eve, to come.

As the sun came up, they began to survey the damage. The surge of water left the town a wreckage with almost everything swept away. Downstream in North Bend, residents began to see debris float by on the Snoqualmie River and knew that something terrible must have happened. North Bend officials sent a train to help with the recovery.

The flood destroyed almost every building, completely obliterating some, and many families lost everything they had. Some of the families decided to leave immediately, while others like Emma and the Tiffins stayed behind to help clean up debris and search for anything worth salvaging.

The owners of the North Bend Lumber Company had hoped to save their mill but the destruction was just too much. They sold what little they could and sued the City of Seattle. In April 1928, after 10 years of fighting, they were awarded $361,867.81.

Although the Boxley Burst, as it came to be known, did not take any lives that night, it did shortly after. Mr. Tiffin, Emma’s adoptive father, cut his leg on some debris while helping with the cleanup. The cut became infected and, in January, took his life.

To this day many residents still refer to the creek as Christmas Creek in memory of that frightful event. You can read Emma Koester’s Letter to her sister, written on Christmas Day 1918, describing both the loss of her husband and town. You can also read the letter she sent to her sister two months later on February 8, 1919.

Visit the Snoqualmie Valley Historical Museum to learn more about this and other Valley stories.