The History of Ski Jumping in the Mountains to Sound Greenway

Although ski jumping in Washington is a distant memory these days, it was the most popular form of skiing in the sport’s early days. The Mountains to Sound Greenway corridor contains several ski jumping sites that were important parts of the country’s tournament circuit, where the world’s best jumpers competed, national distance records were set, and national championships and Olympic team tryouts were held. These include Cle Elum, the Milwaukee Ski Bowl at Hyak, the Kongsberger Ski Club site at Cabin Creek, and Beaver Lake at Snoqualmie Summit.

John Lundin’s latest book, Ski Jumping in Washington: a Nordic Tradition, was written for an exhibit about ski jumping in Washington that will open on April 17, 2021, at Seattle’s National Nordic Museum, cosponsored by the Washington State Ski and Snowboard Museum.

Ski Jumping Originated in Norway and Was Brought to the U.S. by Immigrants

Ski jumping originated in Norway, where it was just a part of normal skiing that children learned at a young age. “Getting from one farm to another in Norway in winter often involves a climb on skis up one side of a hill, and ski jumping developed as a means of clearing obstacles when skiing down the other side.” Harold Anson, Jumping Through Time, a History of Ski Jumping in the United States and Southwest Canada.

“Through the influence of Scandinavians, ski clubs sprouted up all over the northern United States,” initially to the mid-west in the late 1800s, becoming the “thrill sport of winter,” according to Anson. By the end of the 1890s, Michigan had over 30 ski clubs. Jumps were built on small hills with enough vertical drop to provide good landings.

The Northwest has long attracted Scandinavian immigrants, because of its climate, geography and employment possibilities. In Washington, in 1910, Scandinavians were the largest immigrant group, making up 20% of the foreign-born population, and one out of every 20 Seattle residents was born in Norway or was the child of Norwegian-born parents. By 1930, one million people in the U.S. were born in Norway or had Norwegian parents, and 47% lived in New York, Chicago, Minneapolis, or Seattle. According to Anson:

The Norwegians brought to their new country a passion for skiing… They organized ski competitions to strengthen their ethnic ties, showcase their abilities, and generate a new sense of belonging to their new country… It has been said that wherever two or three Norwegians gathered together, they constructed a jump and held competitions. This was never so true than in the Pacific Northwest, as a wave of new clubs showed up along the coastal mountain ranges.

Ski Jumping in Washington

Washington’s earliest formal skiing event took place near Spokane in January 1913. It was organized by Norwegian-born Olaus Jeldness, who made his fortune in the gold fields around Rossland, B.C., and helped create Rossland Winter Carnivals in 1898. In 1913, Jeldness organized Spokane’s first “skee” jumping and “running” exhibition, on what is now Browne’s Mountain, close enough to town it could be reached by inter-urban. The first formal ski jumping event west of the Cascades occurred in Seattle in February 1916, after the heaviest snowfall in decades shut down the city. Norwegian businessmen held a ski jumping exhibition on Queen Anne Hill’s steepest street to demonstrate the sport they brought from their home country.

Seattle’s event was so successful that the local Norwegian community organized midsummer tournaments at Paradise Valley on Mount Rainier, held between 1917 and 1924. Mt. Rainier was “the second place in the world [after Finse, Norway] where the finest skiing may be obtained during the summer months.” The tournaments were “similar in every detail to that practiced in Norway.” Fifty spectators attended the first tournament, growing to 1,500 by 1923.

When the first winter Olympics were held in 1924, at Chamonix, France, only Nordic skiing events were allowed. Alpine skiing first appeared at the 1936 Games in Germany. Publicity about the Olympic Games helped popularize ski jumping in this country.

Between 1924 and 1933, the Cle Elum Ski Club hosted ski jumping tournaments that attracted the best skiers from the west coast and Canada. By 1929, several new ski clubs organized and built steep, competitive ski jumps. This resulted in a circuit of yearly tournaments where the country’s best jumpers competed for the glory of the sport, since they were true amateurs and there were no monetary prizes.

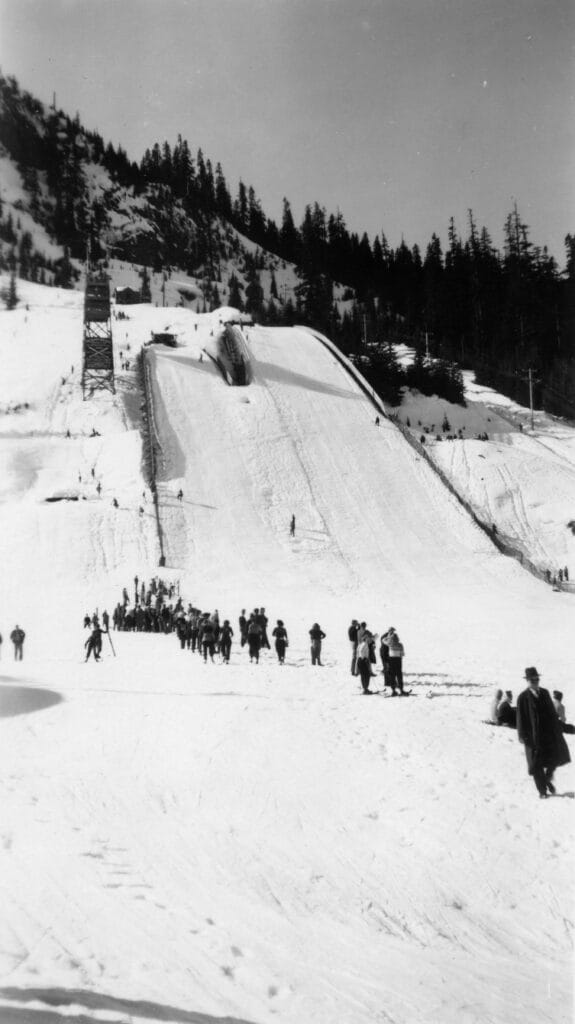

Ski jumping was dominated by Norwegian immigrants, who competed in tournaments at Cle Elum, accessible by Northern Pacific Railroad, whose giant ski jump had “one of the steepest takeoffs in the world,” and was “6% steeper than any in Norway;” Beaver Lake on Snoqualmie Pass, where the jump had “a more tremendous length and pitch than any other hill in the United States;” Leavenworth, accessible by Great Northern Railroad, with “one of the best” hills in North America; and Mt. Hood in Oregon. In 1939, a world-class jumping hill was built at the Milwaukee Ski Bowl at Hyak, opened by the Milwaukee Railroad in 1938, “the biggest and best designed ski-jumping hill available in the United States,” where major national tournaments were held until 1950.

Competitors had to drive long distances on icy roads to reach ski areas, then hike up steep hills through the snow carrying their heavy jumping skis, to reach the jumping sites, and climb steep scaffolds to reach the take-off point. After each jump, they had to hike up the off-run and repeat the process. Tournaments attracted many thousands of hardy spectators, who also traveled long distances, hiked up steep hills, and stood outdoors for hours, often in snow-storms. It was a 1 ½ mile hike from Narada Falls to Paradise Lodge on Mount Rainier. The Beaver Lake jump “lays about 3/4 of a mile uphill” from Snoqualmie Summit, and the hike “is not one to encourage attendance.” Cle Elum’s ski jump on a ridge north of town was reached by a steep, two mile hike.

Ski jumping was seen as adventurous, dangerous and exciting. For non- jumpers, it is terrifying to think of climbing a scaffold high above the ground, then sliding down at high speed, and soaring through the air for several hundred feet. The Seattle Times described ski jumping as “the breath-taking pastime of risking life and limbs on skis.” Jumpers scoff at the idea of being afraid while flying the length of a football field over frozen terrain. Torbjorn Yggeseth, a Norwegian student at the University of Washington and member of Norway’s 1960 Olympic team said:

It’s not really as dangerous as downhill skiing… You’re only going about 60 miles an hour at top speed. As you follow the curve of the hill, you’re never more than 20 feet high. And there are no trees to wrap yourself around. You land at 40 miles an hour. Some skiers land so gently they don’t even leave a mark in the snow.

Washington Tournaments Attracted the World’s Best Jumpers

Newspapers provided extensive coverage of ski jumping tournaments and the battle to set new national distance records. Top ski jumpers were celebrities, much like professional quarterbacks are today. Washington tournaments attracted the world’s best ski jumpers who competed to set new distance records.

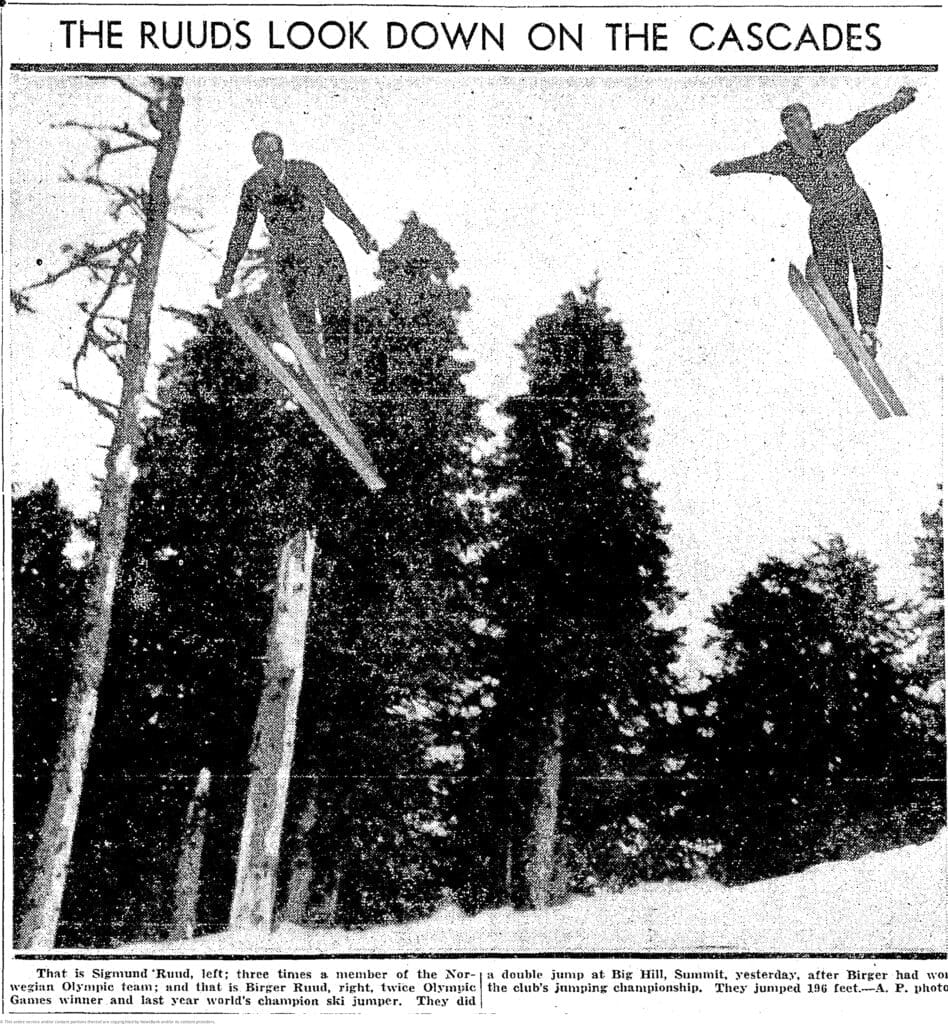

In December 1937, Olav Ulland from Kongsberg, Norway, (“the ski-jumping capital of the world”), came to Seattle to coach ski jumping, and became a mainstay of local skiing. In 1935, Olav was the first to break the 100-meter mark, by jumping 103 meters at Ponte di Legno, Italy. In 1938, the famous Ruud brothers from Kongberg (Birger and Sigmund) competed at Beaver Lake on Snoqualmie Pass, as part of their U.S. tour. Sigmund won a silver medal in 1928 Olympics; Birger won gold medals in the 1932 and 1936 Olympics, and world championships in 1931, 1935 and 1937.

At the 1939 Leavenworth tournament, Olav’s brother Sigurd Ulland (1938 National Jumping Champion) flew 249 feet, a new American distance record. However, later that day, Sun Valley’s Alf Engen jumped 251 feet at Big Pines, California. Then, Bob Roecker of Duluth, Minnesota, jumped 257 feet at Iron Mountain, Michigan. In the jumping portion of the 1940 National Four-Way Championships, Alf Engen beat Torger Tokle, a recent Norwegian immigrant living in New York, in the jumping event at the Milwaukee Ski Bowl, winning the national championship. In February 1941, at Iron Mountain, Alf Engen jumped 267 feet to set a new North American distance record. Two hours later at Leavenworth, Torger Tokle jumped 273 feet. During the 1941 National Jumping Championships at the Milwaukee Ski Bowl, Tokle jumped 288 feet to set his second North American distance record in less than a month, replacing Alf Engen as National Champion. In 1942, Tokle set another new distance record at Iron Mountain, of 289 feet. Tokle was tragically killed in 1945, fighting as a part of the 10th Mountain Division in Italy.

After WWII, a number of Norwegian exchange students entered Northwest schools, led by Gustav Raaum, (winner of Norway’s junior Holmenkollen). They rejuvenated ski jumping, as many of our original Norwegian immigrants were getting older. Raaum, who led the U.W. ski team, said 56 Norwegian exchange students competed for Northwest schools, including 41 in Washington.

In 1947, the Milwaukee Ski Bowl hosted the final Olympic Jumping-team tryouts. Six jumpers were selected for the 1948 St. Moritz Games, coached by Alf Engen. Arnold Kongsgarrd, a visiting Norwegian flyer, jumped 294 feet, exceeding Torger Tokle’s American record by six feet. However, the jump was not official since it was not made during a competition. In 1948, the National Jumping Championships were held at the Milwaukee Ski Bowl. In 1949, Sverre Kongsgarrd, a Norwegian exchange student at the University of Idaho, set a new American distance record of 290 feet at the Ski Bowl, beating Tokle’s 1941 record set at the Ski Bowl and his 1942 record.

The Milwaukee Ski Bowl closed in 1950, after its lodge burned down and the Milwaukee Road decided not to rebuild given the demands of the Korean War. The Northwest lost its nationally famous ski jumps and Leavenworth became the epicenter of Washington ski jumping.

In 1954, “a hardy group of Norwegian ski jumpers,” led by Olav Ulland, Gustav Raaum and others, formed the Kongsberger Ski Club, after the Seattle Ski Club lost interest in jumping and became a cross-country facility. The Kongsbergers built a ski jump at Cabin Creek east of Snoqualmie Pass, held competitions, provided ski jumping lessons, and its members served as tournament officials at Olympic Games and other international events .

In 1956, Leavenworth’s Class A trestle was rebuilt and brought up to new national standards, enabling the club to host national championships in 1959, 1967, 1974 and 1978, and several qualifying competitions for U.S. Olympic teams. Between 1965 and 1970, three new North American distance records were set at Leavenworth.

Interest in ski jumping began to flag in the 1960s, and fell off significantly in the 1970s. Areas with long jumping traditions stopped hosting tournaments: Multopor Hill on Mount Hood in 1971; Revelstoke, B.C. in 1974; and the Kongsberger Ski Club in 1974. In 1978, Leavenworth, “lacking the funds to be re-contoured to meet the revised USSA requirements, shut down after hosting the US Nationals..,” according to Anson.

John is a lawyer, historian and author who has written extensively about Washington and Idaho history. He is a founding member of the Washington State Ski & Snowboard Museum, and his essays about Washington ski history are published on Historylink.org, the on-line encyclopedia of Washington History, and the Central Washington University website for local authors, https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/local_authors/. He is the author of four books: Early Skiing on Snoqualmie Pass (2017)*: Sun Valley, Ketchum and the Wood River Valley (2020)**; Skiing Sun Valley: a History from Union Pacific to the Holdings (2020)*; and Ski Jumping in Washington: a Nordic Tradition (2021).

* Skade book award winner from International Ski History Association; **Skade honorable mention.