The Day Carnation Became the Wild, Wild West

Shootouts with bandits have become the myths of Western movies, but nearly a century ago it happened in real life in the City of Carnation, in a series of events that gripped the region for weeks.

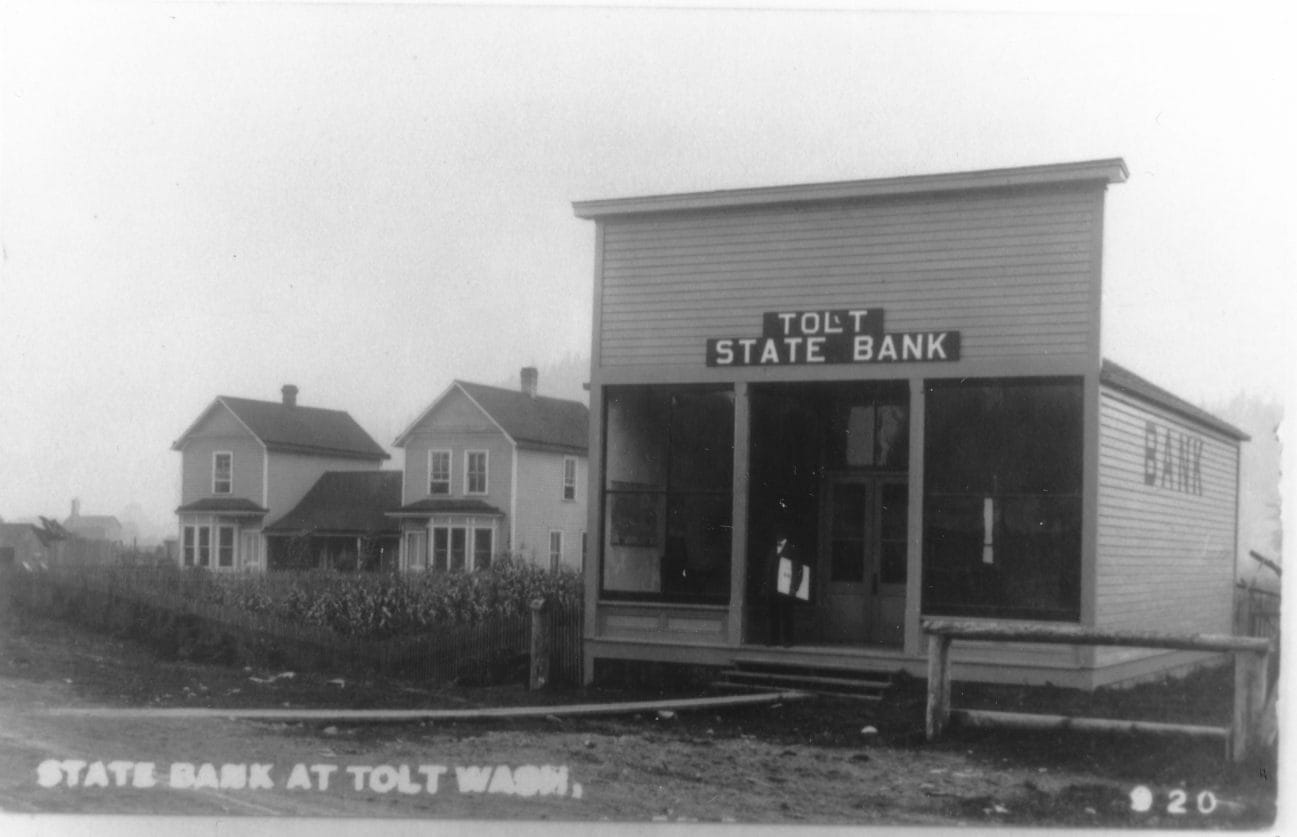

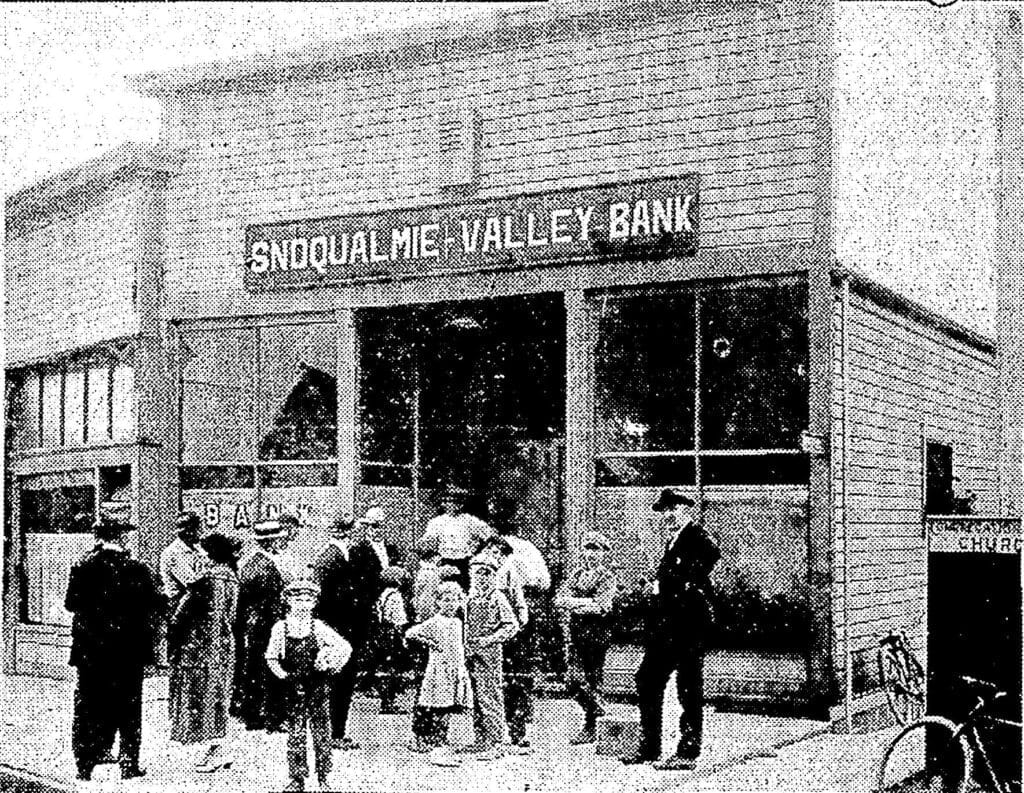

In early August 1924, a major robbery of the Snoqualmie Valley Bank (formerly Tolt State Bank) was being planned. The head “bandit” in the operation, a tough fellow named D. C. Malone, had convinced two of his buddies, Ted Lashe and Jack Bench, to help him pull off the heist. He had actually tried a week earlier to do the job himself, and had even cut the telephone lines of the bank, but then decided not to go through with it until he had back-up. What Malone didn’t know was that Lashe, a part-time private eye, had informed the King County Sheriff of the planned robbery.

Sheriff Matthew Starwich, somewhat of a celebrity in the county, started off his career by helping track down Harry Tracy, an escaped convict who killed six men. Starwich’s work had impressed the Board of County Commissioners, who soon made him a deputy sheriff in southeast King County. Starwich was eventually elected King County Sheriff in 1920. He quickly built a reputation as a tough lawman with a tendency towards (sometimes overly) dramatic takedowns of criminals.

A few days before the robbery was supposed to go down, Lashe had called Sheriff Starwich to let him know what Malone was planning. Starwich, show-off that he was, wanted to catch Malone in the act. Lashe didn’t want to be a part of it, but the Sherriff convinced him to stay in so as not to tip off the others. Confident about his ploy to stop the robbery mid-act, Starwich invited newspaper reporters and courthouse photographers to come to Carnation that day to witness it.

In the early morning of August 13, Starwich gathered six of his deputies and all of the sawed-off shotguns and revolvers from the office, and headed off towards Carnation. On the way they stopped to get shaved. Starwich exclaimed he wanted to be shaved in case they got “bumped off,” while another deputy wanted to look good for the “pictures.” A little after 10:30 a.m. they arrived at the outskirts of the Carnation. Not wanting to draw attention, they split up and slowly entered the town, carrying their guns in bags and bundles. Starwich, already widely known throughout the county, went in through the back streets so that no one would spot him. On his way in he informed the mayor, marshal, and telephone operator about what the expected event.

Bank Vice President Isadore Hall and cashier Ethel Bagwell staffed the bank that day. Starwich explained to Hall and Bagwell about the pending hold-up. Hall agreed to stay and act as cashier and Bagwell headed out for lunch and would not return until the hold-up was over. Three of the deputies hid in a back room of the bank, while Starwich and the other three deputies hid in a shed directly across the street. Hall’s job was to give a signal to the deputies hidden inside when she saw the bandits arrive.

An hour passed, then another, then another, and everyone tried to pass the time and remain calm as they waited for the bandits to show-up. One of the deputies whittled a hole in the shed to pass the time. At one point a herd of cows sauntered down the street, obscuring their line of sight to the bank, causing Starwich to joke, “There’ll be some good beefsteaks in this town tonight if those cows don’t get out of the way soon.”

Finally, just past two o’clock a car pulled up to the bank. Malone and Lashe headed inside while Bench waited for them in the car with the engine idling.

Isadore Hall had seen them drive up and had whispered to the three hidden deputies to get ready. Lashe was first inside. He pointed his revolver at Hall and told her to “stick ‘em up!” She promptly obeyed. Malone swung himself over the counter and headed towards the vault. The three deputies came out of their hiding spots. Malone fired his gun, the deputies returned fire, and soon bullets were flying and the room was filled with smoke. At some point during the exchange Hall had found her way to the vault and closed herself inside.

Lashe still had his gun trained on the scene but had not fired, and this did not go unnoticed. Malone had been hit several times when he received a shot close to his heart and started to stagger backwards. Malone realized that Lashe had not been shooting and must have changed sides, so as Malone fell he shot Lashe and they both hit the ground.

Meanwhile, Starwich and the other deputies had grabbed the driver out of the car and knocked him to the ground with a blow to his jaw. Starwich and the deputies rushed into the bank where the fire fight was already well underway. One of the deputies trained his gun on Malone, who was laying on the ground, badly wounded, and asked “Had enough?” “Enough,” said Malone, who dropped his head and died.

By the time the hold-up was over, the bank looked like a scene from a wild west shoot out: the glass all shot up, Malone dead, and Lashe and one of the deputies wounded. Lashe was rushed to the Snoqualmie Falls Hospital and taken into surgery but died at 7:30 p.m. The wounded deputy was rushed to the Columbus Sanitarium and made a full recovery.

With all the commotion made during the hold-up, nearly the entire town had rushed to the bank to learn what happened and the story quickly spread. Starwich’s invitation to the media meant that reporters on the scene took it all in and photographers quickly snapped photos of the bullet-marked glass and the parties involved.

The next day the story came out in the Seattle Times, spanning four-pages, with a special feature about the heroine Isadore Hall. The story would grip the region, as coverage continued for several more weeks as the driver was questioned and tried.

One of the most controversial parts was the cause of Lashe’s death: although Malone had shot Lashe, an autopsy determined that it was actually a bullet from one of the deputies that had fatally wounded him.

Sherriff Starwich received congratulations from across the country and Canada for his success in “foiling the hold-up.” The original story in the Seattle Times—an entertaining read which comes off as a cross between the Wild West and a gangster movie—is available here. The original building of the bank is still standing today and is the home of Carnation Corners which you can visit on the corner of Tolt Avenue and Entwistle (see photo below). You can also learn more about the history of Carnation (originally named Tolt) from the Tolt Historical Society.