Modern Skiing Takes Shape at the Pass

In our previous blog, we explored the early years of skiing at Snoqualmie Pass up to 1937, characterized by its rough, unplowed roads, the prominence of cross-county skiing and ski jumping, and early forms of downhill skiing where the only way up a slope was to hike.

As the US economy recovered from the Great Depression, new innovations began to change the face of skiing and bring about a new era for Snoqualmie Pass, with mechanized ski lifts, train service from Seattle to the Pass, and the birth of the current Snoqualmie Summit ski area.

1938 was an important year for Northwest skiing with the installation of the first mechanized rope tow. A private company, Ski Lifts, Inc., installed rope tows at Seattle’s Municipal Ski Park at Snoqualmie Summit, as well as Mount Baker and Mount Rainier, eliminating the need to hike uphill and making skiing more accessible.

The Milwaukee Railroad, which connected Seattle with Chicago and the east, opened its own ski area called the Milwaukee Ski Bowl at Hyak, located on the east end of its Snoqualmie Pass train tunnel. The Ski Bowl transformed local skiing with a modern ski lodge, an over-head cable ski lift (a J-Bar), and lights for night skiing. Skiers could travel “safely” by train from Seattle in just two hours. The Seattle Times offered free ski lessons for students, teaching “controlled skiing.”

Skiing in Washington was a $3 million industry, with 20,000 weekend skiers.

With so much demand, Milwaukee Railroad doubled the size of their lodge and expanded the ski hill to provide a mile of skiing. Local ski clubs expanded their facilities as well, with the Mountaineers installing a rope tow at Meany Ski Hut.

Ski jumping continued to be the most popular winter sport in the late 1930s. Tournaments at Beaver Lake on Snoqualmie Pass and Leavenworth attracted the best jumpers in the world to compete, including the famous Ruud brothers from Norway, and thousands of spectators.

In 1940, the US’ top skiers competed in the National Four-Way Championships, held in the Northwest. Downhill and slalom races were held at Mount Baker, the cross-country race at Snoqualmie Pass, and jumping at the Milwaukee Ski Bowl, on a giant ski jump built just for the event. Seattle’s Sigurd Hall won the downhill, and Alf Engen, a Sun Valley instructor from Norway, won the slalom. In the jumping event, Torger Tokle, a Norwegian living in New York, had longer jumps than Engen, but Engen won on form points and won the four-way title. A national ski jumping distance record was set at the Milwaukee Bowl in 1941, by Torger Tokle.

By the early 1940s there were two downhill ski areas at Snoqualmie Pass: the Milwaukee Ski Bowl at Hyak and the City of Seattle’s Municipal Ski Park near the present day Snoqualmie West. Several private ski clubs also provided skiing for their members. In 1940, the City of Seattle decided that Snoqualmie Pass was too remote for a city park. The Municipal Ski Park was taken over by a private company, Ski Lifts, Inc., and renamed Snoqualmie Summit. In 1942, Webb Moffett bought Ski Lifts, Inc.

Before World War II, there were 65,000 skiers in Western Washington, and half a million skier visits at local ski areas, with Mount Rainier attracting the most, followed by the Milwaukee Ski Bowl.

During the War, all local ski areas closed except for Snoqualmie Summit, which stayed open as skiers pooled their gas rations to get there. Army Ski Troops trained at Snoqualmie Summit and Mount Rainier, before moving to Camp Hale, Colorado, in 1943.

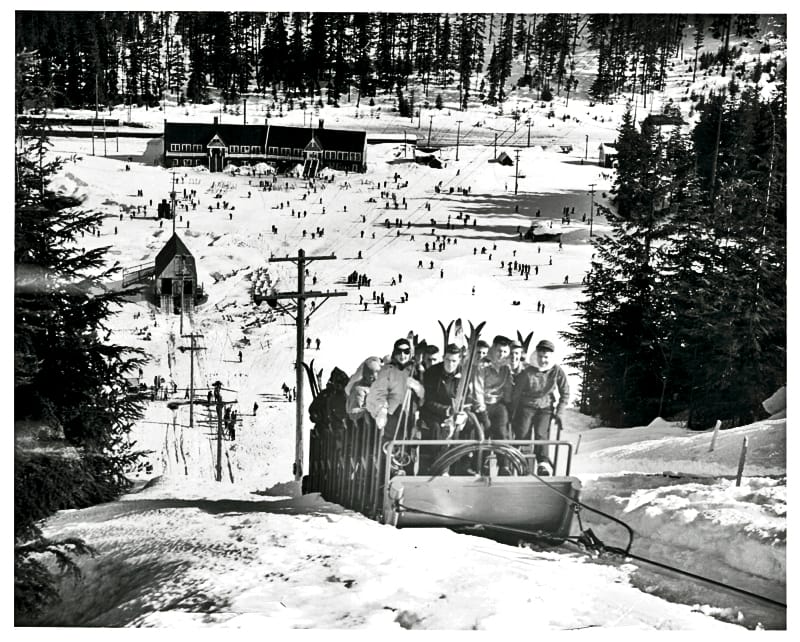

After the war, ski areas were upgraded and new ones built. Snoqualmie Summit installed lights for night skiing. In 1947, the Milwaukee Ski Bowl reopened with a high-capacity ski lift called the SkiBoggan, a 32-person sled carrying 1,440 skiers per hour. Skiers flocked back to the slopes: the Seattle Times free ski lessons were again offered to students, the Ski Bowl hosted the U.S. Olympic team tryout tournament in 1947, and a new generation of Norwegian exchange students dominated jumping competitions.

The following year saw even more improvements and growth. Ski Acres opened one mile east of Snoqualmie Summit, with the first chair lift at the pass. The Mountaineers built a new lodge. The Milwaukee Ski Bowl expanded its slopes and installed new rope tows. Snoqualmie Summit doubled its hill’s length, and had seven rope tows. The Milwaukee Ski Bowl hosted the National Jumping Championships, where three members of the US Olympic team participated, although it was won by a Norwegian exchange student who beat “one of the best fields in American skiing.”

On December 2, 1949, the Milwaukee Ski Bowl Lodge burned down in a $180,000 fire. Milwaukee Railroad decided to close the ski area, ending an era. The Seattle Times cancelled its ski school which had taught 20,000 skiers since 1938.

In 1954, the Kongsberger Ski Club formed to promote ski jumping, and built a ski jump at Cabin Creek east of Snoqualmie Pass. They hosted jumping tournaments for years, but turned into a cross-country club in the 1980s as interest in ski jumping waned.

A Poma lift was installed at Snoqualmie Summit in 1953, and in 1955, the Thunderbird, the first double chair lift on Snoqualmie Pass, was installed, reaching the new mountain top Thunderbird Lodge. In 1959, the Hyak ski area opened near the former Milwaukee Ski Bowl site. Alpental opened in 1967, the fourth ski area on Snoqualmie Pass. Moffet’s Ski Lifts, Inc. purchased Ski Acres in 1980, Alpental in 1983, and Hyak in 1992, then owning all four ski areas.

The Moffets sold their Snoqualmie holdings to Booth Creek Holdings in 1997, which were renamed The Summit at Snoqualmie. The four ski areas became Summit West, Summit Central, Summit East and Alpental at the Summit. In 2006, Booth Creek sold the ski areas to CNL Lifestyles, Inc., but continued as manager. In 2007, Michigan-based Boyne Resorts became the manager and lease-holder of The Summit. Substantial improvements were made to all of the areas.

Learn more about our skiing heritage by visiting the new Washington State Ski & Snowboard Museum at Snoqualmie Pass.

This blog, and other papers on early skiing on Snoqualmie Pass, were written by John W. Lundin, a Seattle lawyer and historian, as part of his work for the new Washington State Ski & Snowboard Museum.

Photo Credit:

SkiBoggan – courtesy of Milwaukee Road Historical Society

J Bar Ski Lift – courtesy of MOHAI

Milwaukee Ski Bowl Lodge – courtesy of Milwaukee Road Historical Society

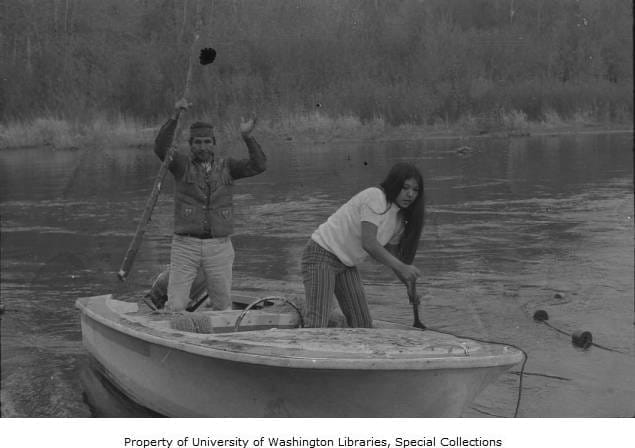

Margaret Odell (the author’s mother, circ 1938) – courtesy of Lundin Family