From Seeds to Trees Across the Greenway — the Lifecycle of our Native Plants

You are volunteering with the Greenway, and you just planted your first Douglas Fir tree. It’s only about 2 feet tall. You can’t help but admire its plume-like branches, vibrant green needles, and rich woody smell. It’s so small that you can’t even imagine how it could become one of the huge evergreen trees you see when you’re out exploring public land in the region.

Believe it or not, even these little trees begin smaller than many of us can wrap our minds around — as little seeds inside pine cones across the forest floor. It is a miracle of nature that these seeds transform into such complex organisms. In the case of Douglas Fir, seeds can grow to become giant conifers 200 feet tall and 8 feet wide!

Greenway volunteers get to interact with native trees and shrubs during their childhood years, something many people aren’t fortunate enough to experience. Still, our volunteers only see one snapshot of the plant’s early life. How seedlings become trees planted in the Greenway is a subject often raised by volunteers, and we think it is worth documenting. A deeper understanding of the lifecycle of our native plants cultivates a greater connection to nature and the work that we do.

Julie Whitacre, Sales Manager at the Washington Association of Conservation Districts (WACD) Plant Materials Center, helps shed light on this topic. The WACD Plant Materials Center is a 60-acre farm in Bow, WA that ships out between 1.5 and 2 million bare root plants per year. It also happens to be where the Mountains to Sound Greenway Trust sources the vast majority of its bare root plants, all of which are potted in our native plant nursery in Issaquah. The Greenway’s AmeriCorps team met with Julie to learn more about how the plants we purchase spend the beginning of their lives.

The native plants we receive from the Plant Materials Center are germinated on-site and live for 1-2 growing seasons on their farm. Approximately 1% of the seeds they plant actually germinate, but there is no mortality after germination. “They all require different conditions for germinating,” Julie explains, “some of them we stratify in the cooler, some we plant in the fall, and others we plant in the spring.” They operate as a wholesale nursery, so they ship throughout the state to large buyers such as land trusts, regional conservation districts, and fisheries enhancement groups. Some of their seeds, like serviceberry and pacific ninebark, are harvested from mature plants on the farm, but most of their Western Washington seed comes from another nursery called Plantas Nativa, LLC.

The seeds they purchase are chosen not just according to species, but also according to the “seed provenance” that each species originated from. Seed provenance refers to the area in which the plant that produced the seed was harvested. Through thousands of years of natural selection, plants of the same species began to adapt to their own regional environment.

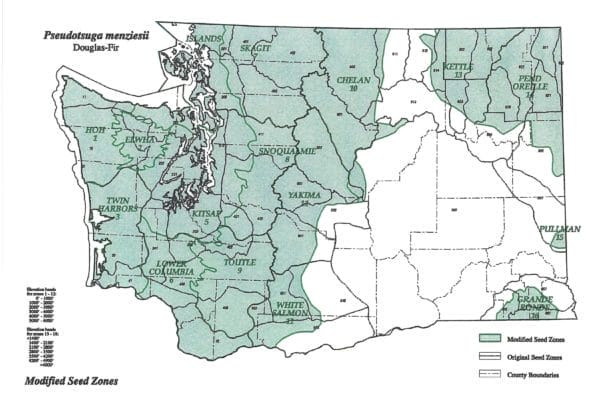

All the native shrubs we receive come from Western Washington. If their seeds had been originally harvested in Eastern Washington, they would be less accustomed to the wet climate and therefore more susceptible to various fungal diseases. Conversely, planting seeds from Western Washington in Eastern Washington would result in those plants being less likely to survive the cold, harsh winters. Coniferous trees in the Pacific Northwest have even smaller, more specific boundaries for where seeds are sourced from. These “transfer zones” were originally drafted in 1966, after foresters discovered that reforestation projects were more successful when seeds were sourced properly.

The map (right) shows, for example, the delineation of Douglas Fir seed zones in Washington State. The Douglas Fir trees we buy from the Plant Materials Center are from Zone 412, which is actually outside of the Greenway, near Mt. Rainier. In an effort to proactively adapt to the effects of climate change, some of the plants we purchase – like Douglas Fir – were harvested in zones south of their properly designated planting zone. As average temperatures increase, current zoning will likely become obsolete by the time our trees are fully grown.

So, the Plant Materials Center receives seeds from a variety of zones, then sells those plants according to the region in which they are going to be planted. The bare root plants we purchase are then potted up at our native plant nursery and live there for another 1-2 growing seasons. Mortality can occur, and losing 15% of our potted plants in the first year is not unusual. By the time the potted plants are transplanted into restoration sites across the Greenway, they are between 2-4 years old. Each plant’s success depends primarily on the quality of the planting and whether it can adjust to new soil conditions.

While so much happens before our plants even end up in the Greenway, planting is really just the beginning. Simply clearing invasives and planting trees is not enough to restore an area. Left alone, sites with young plants can easily become overtaken (or re-overtaken) by invasive species. The success of habitat restoration depends heavily on long-term care and maintenance. Our volunteers and crews continue working on the same sites for years in order to ensure that our native plants live long, healthy lives. In areas like the Middle Fork Snoqualmie Valley and Lake Sammamish State Park, the Greenway has been monitoring and maintaining native plant cover for decades.

Ensuring the success of each plant – from seed to adult – requires an incredible amount of thought, dedication, and care. Our volunteers care for native plants in the Greenway at all the various stages of their lifecycle. Many get to hold young plants in their hands and feel a greater connection to the ecology of the Pacific Northwest. Some (the luckiest ones) get to return to sites they worked on 10, 20, maybe 30 years ago to see how their plants have matured. All of us get to experience and enjoy restored lands throughout this region.