Applying the Breaks: How Wildfire Resilience Work Curbed the Labor Mountain Fire

Fighting wildfires in Washington State costs an average of one million dollars a day, but there’s a much cheaper, more effective way to prevent their spread in the first place: wildfire resilience work. Implementing fire-wise projects like shaded fuel breaks allows land managers to be ready instead of reactive. Take the Labor Mountain Fire as a case study.

Last fall, the 2025 Labor Mountain Fire burned nearly 43,000 over the course of 52 days (1). It singed a hole into the Mountains to Sound Greenway map that Seattle could fall through. Thousands of people across dozens of teams worked to curb the fire. Through it all, one boundary remained contained: the southwestern line along Stafford Creek, where the Washington Department of Natural Resources (DNR) recently completed a fire-wising project in the Teanaway Community Forest (TCF). The TCF managers spent $1,800 per acre to install this shaded fuel break earlier in 2025, which protected countless resources in the 50,000-acre community forest and beyond, all while preserving forest health.

Yet, here in Washington, we continue to see funding for preventative work through the Wildfire Response, Forest Restoration, and Community Resilience Account slashed. Here’s why you should care, and how you can help.

How the TCF Shaded Fuel Break Helped Curb the Fire

Where larches once shimmered gold among the pines, an atmospheric river trenches the sooty hillsides. The drive from Cle Elum to Blewett Pass is a patchwork of grey, black, and green, stitched with dark snags and burnt trees, like a barn quilt showcasing the aftermath of wildfire.

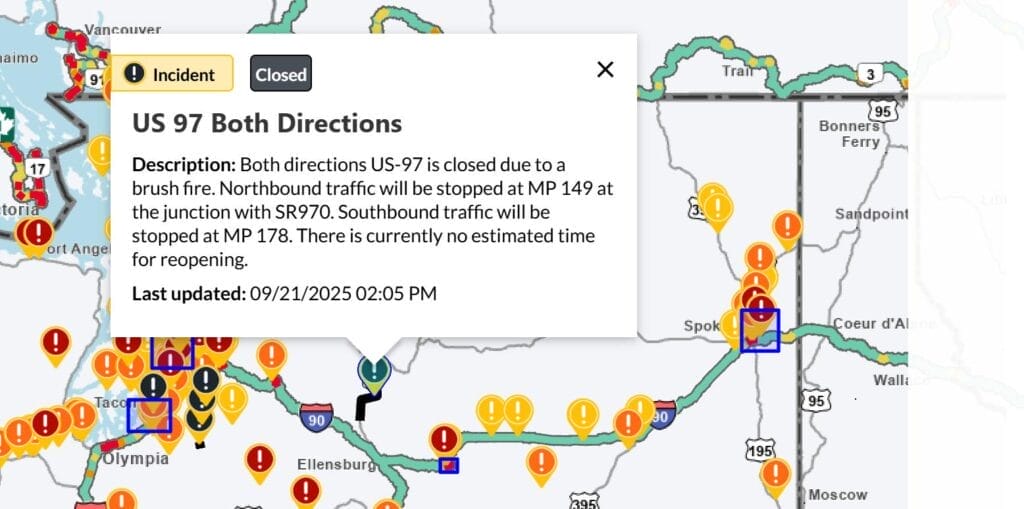

The fire started with a lightning strike on Labor Day on Labor Mountain—about ten miles from Cle Elum. In late September, evacuation orders were issued to the northeast as the fire leaped Highway 97 and forced the closure of Blewett Pass. At its height, on a single day, the Fire Incident Management Team deployed 1,500 people on over 40 crews, alongside 71 engines, 14 helicopters, 36 heavy equipment, and 31 water tenders (2).

Fighting the Labor Mountain Fire cost taxpayers roughly $52 million, but it can take years to fully account for the direct costs associated with a fire this size. Once the fire was contained in late October, NW Fire Crews transferred it back to local units with the Okanagan Wenatchee Forest, Bureau of Land Management, and DNR for stabilizing work.

Despite the size and severity of the Labor Mountain fire, the towns in Upper Kittitas County that were initially most worried about the fire’s risks emerged safe from all except the smoke. They have the shaded fuel break to thank.

The Labor Mountain Fire’s southwestern perimeter held—while the fire exploded to over 40,000 acres—along Stafford Creek, where the Teanaway Community Forest recently installed a shaded fuel break.

The TCF is co-managed by the Washington Departments of Natural Resources and Fish and Wildlife. They use the input of a community advisory committee to leverage local partnerships, engagement, and investments with state funding. In 2025, the TCF managers contracted crews using funding from the Wildfire Response, Forest Restoration, and Community Resilience Account (Wildfire Resilience Account) to implement an additional shaded fuel break, continuing past forest health work.

What is a shaded fuel break?

A shaded fuel break is an accessible stretch of forest where land managers strategically reduce fuels to create a line of defense. To create these lines of defense, foresters and contractors thin stands of trees. They leave the oldest and healthiest standing while removing ladder fuels (lower limbs and underbrush that would help a fire climb into the tree canopy), duff, and downed logs.

Unlike firebreaks, shaded fuel breaks preserve vital vegetation. They are created along key lines, anchored to barriers (like roads, rivers, and ridgetops), and break connected areas of dense timber. This placement cuts off fuel bridges to protect infrastructure and habitats. A shaded fuel break ensures that when a wildfire reaches the area, it will be less intense, easier to fight, and less likely to reach the canopy or scorch the soil (3).

It serves another role, too. Beyond being a precaution against wildfire, shaded fuel breaks can be a regenerative technique for preserving forest health and resilience. They protect forests from diseases caused by overcrowding and prompt the growth of certain species, like native wildflowers.

Being responsible for both land management before a fire and for responding to fires themselves puts DNR in a unique position to see the effects of shaded fuel breaks. “As a land manager, we’ve been able to use this opportunity to improve and protect the forest and all the benefits that the forests provide,” says DNR State Lands Assistant Southeast Region Manager Larry Leach. “Also, being a firefighter, having the fuel breaks in place before the smoke is in the air gives us a jump on containment and reduces the acres burned, along with the duration of the fire. That saves costs, allows for less disruption to nearby homes, and minimizes smoke impacts.”

The North Fork Teanaway Project

To protect the Teanaway Community Forest and its neighbors, Washington DNR put funds from the Wildfire Resilience Account into creating a shaded fuel break up the North Fork Teanaway to Stafford Creek. That area borders largely untreated National Forest land to the north, which accounts for most of the land burned in the Labor Mountain Fire. The TCF land managers treated 69 acres there. They spent about $124,000 (or $1,800 per treated acre) to protect the 50,000-acre community forest—less than a quarter of a percent of what fighting the Labor Mountain Fire cost.

“That prep is done ahead of time, not when there’s smoke in the air,” says Leach.

Trees in the fuel break—within 100 feet from the road—were thinned to stand roughly 16 feet apart. Remaining trees were pruned up 10 feet. Usually, downed branches, brush, and trees were chipped, but some of the woody material was also used by Mid-Columbia Fisheries to do in-stream restoration work, an innovative way to aid the Teanaway Community Forest’s river restoration efforts.

“The shaded fuel break work created a real opportunity to think beyond fire risk alone,” says Mike Bosko, the Upper Yakima Project Manager for Mid-Columbia Fisheries Enhancement Group. “Working collaboratively with DNR and WDFW, we repurposed thinned trees as instream wood, improving stream function and habitat while supporting broader forest-health goals. It’s one way that investments in fire-wising can directly benefit watershed restoration.”

During the Labor Mountain Fire, fire crews were able to strengthen the Stafford Creek fuel break and extend it onto Forest Service lands. The TCF shaded fuel breaks provided firefighters with options: while Stafford Creek was identified as a Potential Control Line (PCL) to hold off the fire early on, Jack Creek served as a contingency line in case high winds caused the fire to jump the Stafford Creek line.

The shaded fuel break along Stafford Creek was a continuation of work along the North Fork Teanaway Road—one of many forest health and fire-wising treatments in the TCF aligned with DNR’s 20-Year Forest Health Strategic Plan. Forest health treatments like these give firefighters more options while laying the groundwork for more management options, like using controlled fire, in the future. It’s vital to do this work before, not during, disasters.

Fire Suppression: Ready vs. Reactive

When preventative work isn’t done ahead of an emergency, it still has to be done during the emergency. While planning for a shaded fuel break, land managers and foresters can choose areas where applying fire-wising techniques is less expensive. During an active wildfire, though, it’s the fire that chooses where work must be done, often on steep, inaccessible landscapes that require specialized hotshot teams, equipment, and helicopters.

Fighting a major fire demands the expertise, dedication, and sacrifice of thousands of firefighters and emergency responders. State and federal employees, volunteers, and out-of-state teams protect our landscapes and communities, leaving their homes and families for weeks at a time to operate out of mobile fire camps.

Techniques used on the Labor Mountain Fire

Specialized hotshot crews: on October 8, 13 hotshot crews were deployed simultaneously

Structure protection, like portable tanks and pumps for sprinklers or wrapping infrastructure in flame-resistant materials

Unmanned Aerial Systems (UAS), AKA drones, for fire surveillance, scouting, and fire ignition

Heliwells: 15,000-gallon portable tanks for helicopters to draw water from when nearby water sources aren’t deep enough

Tactical burning or firing operations, which bring fire to primary containment lines

Masticators and chipping operations to improve road access and fire lines

Water drops from Type 1 heavy helicopters and SuperScooper planes

Hand lines to assist ignitions on steep terrain

Rapid Extrication Module Support (REMS), a skilled technical team cross trained in medical, technical rope rescue, ATV/UTV operations, and extrication in rugged environments

Fixed-wing plane fire retardant drops

Removing hazard trees with saw crews

Digging fire line

Dozer lines

Hoselays

Water bars

Costs of the Labor Mountain Fire

The total costs and economic impacts of major wildfires like this one extend far beyond the $52 million paid by taxpayers and those borne by emergency responders. The costs of reacting to wildfire also include: the destruction of habitats and rangeland; the relocation of people and animals during evacuations; loss of business; coordination with local law enforcement; recreation infrastructure; and water.

On October 4, heavy helicopters dropped 151,000 gallons of water on the Labor Mountain Fire’s perimeter. That’s nearly half an acre foot, or what it takes to grow over a ton of hay in a season (4). This was just a drop in the bucket. Hundreds of thousands of gallons were dropped over the course of the fire. In 2025, Kittitas County had entered its third consecutive year of severe drought, and a temporary ban on surface water use was issued on October 6 in a historic emergency restriction. Drawing on this much water to fight fires has a direct impact on irrigators, salmon, and communities that rely on surface water, like the towns in Upper Kittitas County.

Furthermore, burned acres are far more vulnerable to landslides and mudflows (5), like those sparked by the waves of atmospheric rivers that hit the Pacific Northwest in early December 2025. When our state chooses to invest in shaded fuel breaks and preemptive fire-wising efforts, we can choose cheaper acres to work on, saving money while sparing landscapes, communities, and water. As seen in the Labor Mountain Fire, this investment pays enormous dividends.

A Pattern of Success

The 2025 fire perimeter along Stafford Creek’s shaded fuel break isn’t the first instance of fire-wising efforts in the TCF protecting landscapes and nearby communities. During the 2017 Jolly Mountain Fire, a similar perimeter was maintained in the TCF along the Lick Creek shaded fuel break. The Jolly Mountain Fire burned for three months on nearly 37,000 acres, threatening over 3,800 homes. In September of 2017, ash fell “like snow” on Seattle; Kittitas County declared a State of Emergency; and Cle Elum developed a contingency plan for evacuation, but ultimately it was stopped before the Cle Elum Ridge (6). The communities of Ronald, Roslyn, Cle Elum, and South Cle Elum were protected.

The fire was contained before reaching these communities largely because of fire-wising efforts made by TCF land managers (funded through the Capital budget), further buffered by forest health work conducted by The Nature Conservancy on the Cle Elum Ridge. The success of projects like this—and the science confirming their impact—fueled support for more preventative and resilience-focused work.

In 2021, the Washington Legislature unanimously approved HB 1168 to establish the Wildfire Response, Forest Restoration, and Community Resilience Account (Wildfire Resilience Account). DNR administers this account to fund programs that restore forests, support local governments and firefighters in responding to fire, and give people and ecosystems the tools they need to recover from fire.

You can learn more about wildfire resilience and forest health work specific to the dry forests of Central Washington from our partners at The Nature Conservancy and Chelan County (7). Fires will happen, but their impact can be lessened by proactive programs, like those funded through the Wildfire Resilience Account.

Support Funding for Preventative Work

The establishment of the Wildfire Resilience Account had unanimous approval. Yet each year, the actual budget for wildfire funding has been slashed. The initial commitment that the Washington Legislature made was $125 million for four biennium. In the third biennium, that funding was reduced to $60 million, with only $20 million allocated this last year.

This reduction in funding is out of step with the fact that preventing fire is far more cost-effective than fighting fire. Washington State Commissioner of Public Lands Dave Upthegrove visited the Labor Mountain Fire Incident Command Post for a press conference about fires in the region on October 1. He emphasized that investing in Wildfire Resilience has immediate payoff: “This isn’t about saving money 50 years down the road: the amount the state of Washington pays in response and recovery can be reduced by investing in preparation and prevention.”

It’s a sentiment that Representative Tom Dent has voiced many times. In the state legislature, Dent represents District 13, which includes the Teanaway area in Kittitas County. Representative Dent also hosts the Wildfire Caucus and is advocating for restored funding to the Wildfire Resilience Account in the coming legislative session.

The long-term health and safety of the Mountains to Sound Greenway depends on proactive measures like those funded by the Wildfire Resilience Account. If you would like to advocate for Wildfire Resilience in Washington State, too, you can:

- Encourage your legislator to restore the Wildfire Response, Forest Restoration, and Community Resilience Account and sign the related Dear Colleague Letter

- Attend a Lobby Day to support related legislation

- Share DNR’s legislative priority sheet

- Schedule testimony for these Statement Bills “requesting Congress to ensure that federal wildfire response entities have the capacity to protect communities and infrastructure, limit impacts to natural resources and watersheds, and protect wildland firefighter health and safety”

Join the Mountains to Sound Greenway Trust and our partners in advocating for restored funding to “apply the breaks” on wildfire. Learn more about our advocacy efforts here.

Sources and Further Resources

(1) The Labor Mountain Fire burned 42,967 acres from September 1st through October 23rd. You can watch the perimeter growth on Wildfire Trackers: Labor Mountain Fire Active Wildfire.

(2) All fire numbers are pulled from the Fire Incident Command Team Daily Reports. The 14 helicopters on October 7th were co-assigned to the Lower Sugarloaf Fire. All photos without otherwise indicated photo credits were pulled from the Labor Mountain Fire 2025 Facebook page.

(3) Learn more about shaded fuel breaks: Distinct from firebreaks; created along key lines; and scientifically proven to lower the impacts of fire.

2023 Forest Ecology and Management, Vol. 543, “Quantifying the effectiveness of shaded fuel breaks from ground-based, aerial, and spaceborne observations” by Janine A. Baijnath-Rodino, Alexandre Martinez, Robert A. York, Efi Foufoula-Georgiou, Amir AghaKouchak, and Tirtha Banerjee: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2023.121142

(4) Estimated water use on a hay farm in Kittitas County is 1.5-to-2 acre feet applied per acre per year. Sources used to calculate this comparison were: 1) the 2023 national average of acre feet applied per acre, USDA (1.5): 2023 Irrigation and Water Management data now available (and a 2025 explanation for why there isn’t a more recent national average, USDA: USDA Reschedules Reports Affected by Lapse in Federal Funding); 2) a hay-specific estimation of water use by Montana State University: Making A Ton of Hay! – MSU Extension Water Quality | Montana State University; and 3) Kittitas-Valley-specific estimations by Washington State University, 1998, which found 2 acre-feet for wheelline irrigation systems: THE ECONOMICS OF ALTERNATIVE.

(5) Assessments of landslide risk due to the Labor Mountain Fire: 2025 Labor Mountain Fire WALERT Report (DNR) and Word FAQ Template (USFS).

(6) Read more about the 2017 Jolly Mountain Fire: Seattle Times article about homes at risk; ash falling “like snow”; and Cle Elum’s contingency plan for evacuation.

(7) Learn more from partner StoryMaps about forest health and resilience in Central Washington/dry forest ecosystems: From Overgrowth to Renewal | The Nature Conservancy and Chelan County Wildfire Resiliency Tour.

You can also explore DNR’s Forest Health Tracker, review the Teanaway Community Forest’s goals, and learn more about DNR’s 20-Year Forest Health Strategic Plan.